Did anybody expect Brian Kemp to veto Georgia’s school recess bill?

After fighting for three years for elementary school recess in Georgia, state Rep. Demetrius Douglas, D-Stockbridge, told colleagues in the midst of his most recent attempt, “I never thought recess would be this difficult.”

Douglas had no idea of the difficulty ahead. Because even after the recess bill won passage this session with overwhelming bipartisan support, Gov. Brian Kemp shocked many supporters of the legislation and vetoed House bill 83 Friday. The legislation would have mandated recess for kindergarten through fifth grade.

While Kemp agreed recess is important, he felt the bill undermined local control in education. "This legislation would impose unreasonable burdens on educational leaders without meaningful justification," explained Kemp. (Kemp was more tactful than New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie who, after vetoing a recess bill in 2016, said, "That was a stupid bill." Two year later, Christie's successor signed the bill.)

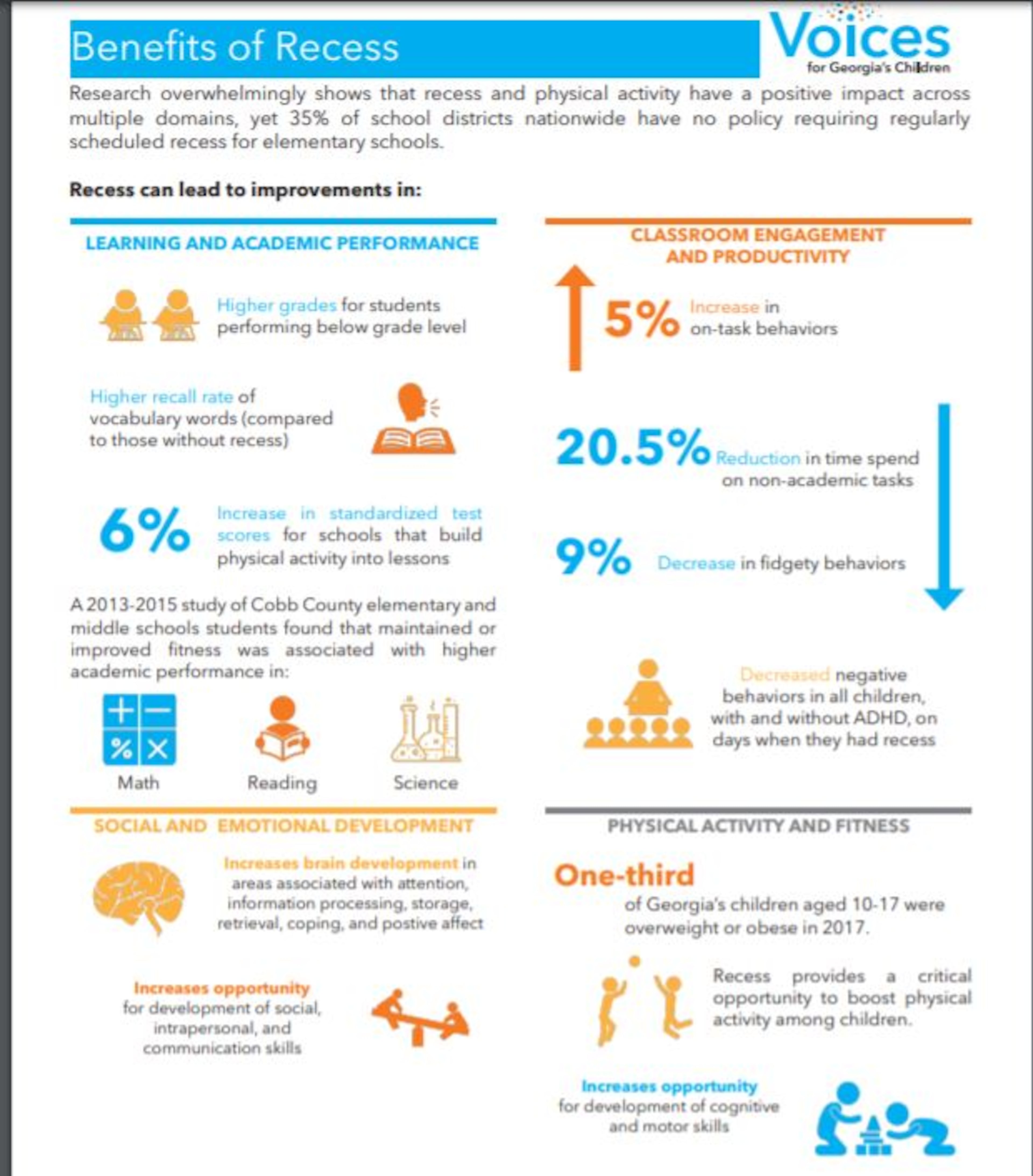

School recess lost ground after the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act prioritized math and reading scores. Forty-four percent of America's school districts reported cutting time from other areas, including recess, art and music and physical education, to beef up math and reading instruction.

A generation ago, schools set students loose on the playground for an hour to hang with friends or on monkey bars. Now, recess is a 10-to-30 minute break in the day, and often not outside the school building. It's also become a discipline tool. Nearly two-thirds of principals reported in a 2009 survey that they took away recess as punishment for behavior problems or not finishing work.

There is no federal requirement for recess as it’s viewed as a state matter. Five states mandate recess, while at least seven states require daily physical activity for elementary schools. In every case, legislators in those states expressed fears over the increasing sedentary lifestyles of children. Georgia has the 18th highest obesity rate for youth ages 10 to 17

A strong push for recess is coming from parents, who contend unstructured play is vital to children’s physical and social advancement. Those parents found allies among child development researchers who say recess bolsters social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development.

Among them is retired Georgia State University professor Olga Jarrett, a longtime advocate for recess who told the Legislature this year that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention encourages recess for middle and high school students, not just elementary pupils.

The campaign for mandatory recess has dragged on for so long that one of the first kids to testify in its favor will start middle school in August. As a second grader, Pierce Mower of Atlanta showed up at a school board meeting to urge daily recess. About to complete fifth grade, Pierce came to the Gold Dome this year to endorse not only mandated recess for elementary school children, but for middle school students, too.

Pierce said some of his classmates did not meet their reading goals and lost recess as a consequence. “They have to sit out the whole recess reading and I don’t think that’s really helpful and no one deserves that,” he said.

In presenting his bill to his colleagues in the Senate in March, Douglas said he made some changes to appease their concerns so there would be “no more heartburn” over his bill.

Douglas might have warded off heartburn in the Senate, but he still ended up with heartache from the governor.