In blaming schools for eroding reading skills, are we overlooking surge in children’s screen time?

In decrying disappointing U.S. reading performance, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos looked at what occurs within schools, citing ineffective teachers, antiquated approaches, bloated bureaucracies, overpaid administrators, bad policies and "Big Ed."

She didn’t reference what’s happening outside schools -- a seismic shift in how American children spend their time. Increasingly, they are parked in front of screens.

The time children now devote to television, laptops, tablets and phones once went to other activities. Isn’t it logical to assume reading was one of them?

Instead, DeVos seized on the stagnate and declining reading scores to urge more “education freedom" in the form of charter schools, tax-credit scholarship programs, education savings accounts and vouchers.

What DeVos didn’t endorse was more investment in our schools. "It’s way past time we dispense with the idea that more money for school buildings buys better achievement for school students," she said.

The education secretary skirted any data that would undercut her exaltation of choice and privatization. For instance, a bright spot in this year's National Assessment of Educational Progress, better known as the Nation's Report Card, was the performance of students in the traditional public schools in Washington, D.C.

Released two weeks ago, the 2019 NAEP reading and math scores in fourth and eighth grade show gains by students at higher-academic levels but no progress or declines among lower-performing ones. Every two years, NAEP tests a sampling of 4th and 8th grader in reading and mathematics.

DeVos’ response to NAEP ignores what many experts suggest could be a key factor in the decline of reading scores -- the residual impact of a recession that dramatically reduced school budgets.

"Twenty-nine states still spend less on education then before the Great Recession," said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers. "Fifty years ago, when robust, focused investments in our schools were this country's top priority, unlike now, we saw changes like faster growth and more significant gains in the way our students were achieving. But today's NAEP numbers are a reflection of a very different model: When we under-resource our public schools and divest in high-quality public education, our kids suffer."

Mike Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, also pointed to the recession, saying big shifts in the economy—both booms and busts— appear to affect the later achievement of babies and toddlers who live through those changes.

He wrote: “With parents jobless, stressed out, and struggling to make ends meet, it’s not hard to imagine that the little ones would get less care and attention in all the ways that we know matter to their cognitive and social development.”

In surveying students, NAEP found greater than 9 in 10 have access to a computer, tablet, or smartphone at home. And most have more than one such device at their disposal.

A long time ago, an expert told me that if you want to prod your kids to read, fill the house with good books. I am not sure that’s true now that houses are also full of tantalizing screens and all three seasons of "Stranger Things."

I reached out to Petrilli to ask if he thought screen time could be eroding reading skills.

“Yes, I think it’s possible. Though what we see happening in most subjects and grades is that kids toward the top of the achievement spectrum —75th and 90th percentiles — are doing pretty well,” said Petrilli.

“It’s the lowest achievers — 10th and 25th percentiles — who are really doing much worse. Sadly, those are also, in general, the poorest kids,” he said. “So would screens hurt their achievement but not their higher achieving, often wealthier peers? Given how ubiquitous screen use is?”

Petrilli posed a good question.

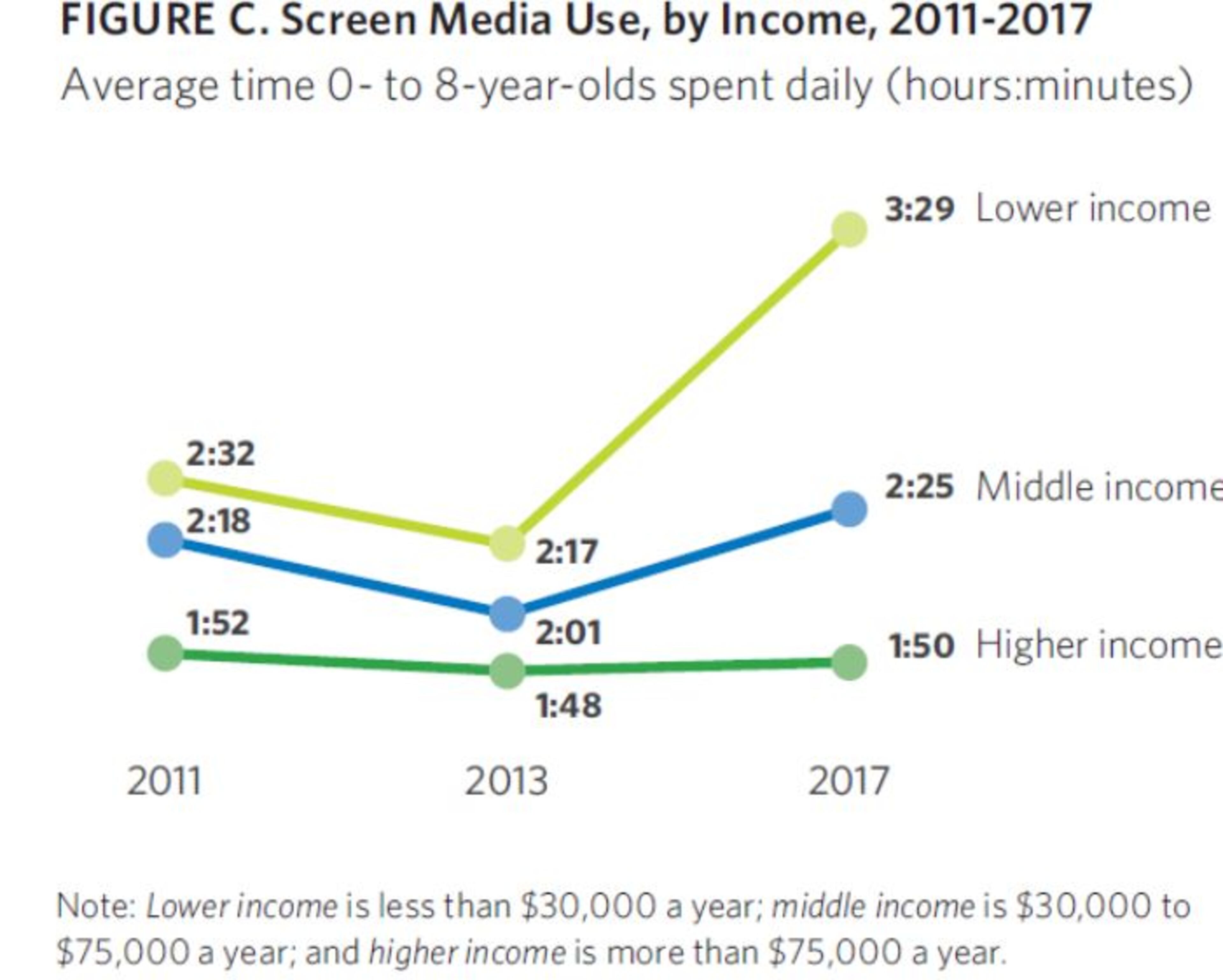

Common Sense, a leading chronicler of how much time kids are in front of screens, broke down screen time by family income in its 2017 report, "Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero To Eight."

For children in high-income households, screen time remained consistent from 2011 to 2017, about an hour and 50 minutes a day. It has also remained fairly stable among middle-income kids, 2 hours and 25 minutes.

However, among low-income children, time given over to screens soared, from 2 hours and 32 minutes in 2011 to 3 hours and 29 minutes in 2017.

Common Sense noted: "The reason the gap has grown larger is that in 2017, lower-income children’s television use has gone up (along with their use of mobile media), but higher-income children’s television use has gone down. On any given day, more lower-income kids watch TV now than did four years ago (58 percent vs. 42 percent), and those who watch TV spend more time doing so (2:23 vs. 2:02)."

Looking at all the young professionals around me, I observe a lot of time and money going into their children’s enrichment. It may be these educated parents limit screens more.

In addition, research on child care in America shows that lower-income parents tend to rely more on family members to watch their kids. Could it be that tired grandparents may not fight their grandchildren over another episode of “Paw Patrol,” unlike the paid nannies and after-school sitters schlepping 5-year-olds to piano, soccer and dance?

Education Week delved into screen usage this month, including how screens are now incorporated into learning and reading in our classrooms. (Read the piece; it is excellent.)

Ed Week found “that in both grades 4 and 8, spending more time using a computer or digital device for English and language arts work was associated with lower reading proficiency on the test...And the link between more digital time and lower scores in language arts was even stronger, based on a separate study of 2017 NAEP data from high-poverty schools.”

Your thoughts?