Green Book exhibit rides into Carter Library and Museum

Meredith Evans remembers how her mother, Rochelle Whitaker Evans, would tell her stories about traveling from New York City to tiny Enfield, North Carolina, as a child in the 1950s.

Alexander Whitaker would meticulously plan the family’s route to make sure he knew which restaurants, gas stations and hotels would be friendly to Black travelers.

“I never take for granted what my elders did for me to have the life I have now,” said Evans, the director of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library & Museum.

Last weekend, the Carter Library and Museum debuted its newest exhibition, “The Negro Motorist Green Book.”

Developed by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and curated by historian Candacy Taylor, the exhibit is a story of mobility and how Black people had to plot and plan for safe navigation across a country steeped in Jim Crow laws.

Original artifacts include actual Green Books, business signs and postcards, as well as archival photos, videos and first-hand accounts from mid-century America on how the annual guide served as an important resource for the country’s rising Black middle class.

Taylor, who has been researching and archiving “The Green Book” since 2013, said of the roughly 11,000 sites that have even been featured in the guide, fewer than 5% remain in operation.

“When you walk into the space, you’re going to get a real sense of what it looks like to travel and vacation, and have family time as an African American during that time period,” Evans said. “And it’s really quite fascinating.”

The safest way

On Friday, Tony Clark, the director of public affairs for the library, made his way through the maze-like exhibit, which runs through June 23. He stopped at an interactive display that simulated driving in a car.

“I hope this is an eye-opener for a lot of people to understand just how difficult it was to get from one place to another in this country, and what an asset ‘The Green Book’ was for people who were traveling during the Jim Crow era,” Clark said.

In the interactive car, once everything is checked in the trunk, a hypothetical family plans a trip from Chicago to grandma’s house in Huntsville, Alabama. Today, it is roughly 581 miles down I-65.

But during Jim Crow, the family would have had to choose between the shortest route, about 550 miles through the rural countryside with few stops approved by “The Green Book” or take a longer 625-mile route with more access to friendlier sites.

“By having ‘The Green Book’ you could figure out the route that you needed to go so that it’s the safest way to get food, gas and a place to sleep,” Clark said. “That may not be the quickest way to get there. But what is more important is what is the safest way.”

Jim Crow lived throughout the country

“The Green Book” was not the first travel guide for Blacks. Between the 1930s and 1970s, there were at least a dozen Black travel guides, Taylor said.

But thanks to the marketing genius of its founder, Victor Hugo Green, “The Green Book” was the most enduring, running for 30 years.

A Harlemite, Green published the first “Green Book” in 1936, just as the automobile was making it easier to travel.

It focused primarily on New York City spots. Green lived with the Black intelligentsia in the Sugar Hill district, down the street from Louis Armstrong. But even in the wake of the Harlem Renaissance, there were still places along 125th Street where Black people were not welcomed.

“So it was very much a problem he was trying to solve in his own community,” Taylor said of that first edition. “It’s an answer and a solution to the extreme violence that Black folks were encountering during their travel, and places that they had just been shut out of.”

By 1937, Green had expanded his vision, and included places all over the country that were friendly to Black visitors and travelers.

Taylor said there is a popular misconception that “The Green Book” was needed and used only in the South.

“Our exhibition really complicates that assumption and shows you different parts of the country where ‘The Green Book’ thrived and was necessary,” Taylor said. “Racism and Jim Crow lived throughout the country.”

In his guide, Victor Hugo Green highlighted restaurants, hotels, drug stores, funeral homes, movie theaters, nightclubs, skating rinks and even Black colleges.

Esso Standard Oil, one of the few nationwide service stations to serve Blacks, sponsored and sold “The Green Book.”

“There’s a democratization and a real broadening of what Blackness is,” Taylor said. “There were all different kinds of Black people, in all different classes, using ‘The Green Book.’ Atlanta really gets that because there’s so much diversity within Blackness in Atlanta.”

Space in Atlanta

As shown in the exhibit, a simple stroll down Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue offers a glimpse at what could be expected from reading “The Green Book.”

It would have told a Black traveler that they could stay at the Butler Street YMCA or the Waluhaje Hotel Apartments. Then they could get their hair cut at the Gate City Barber Shop.

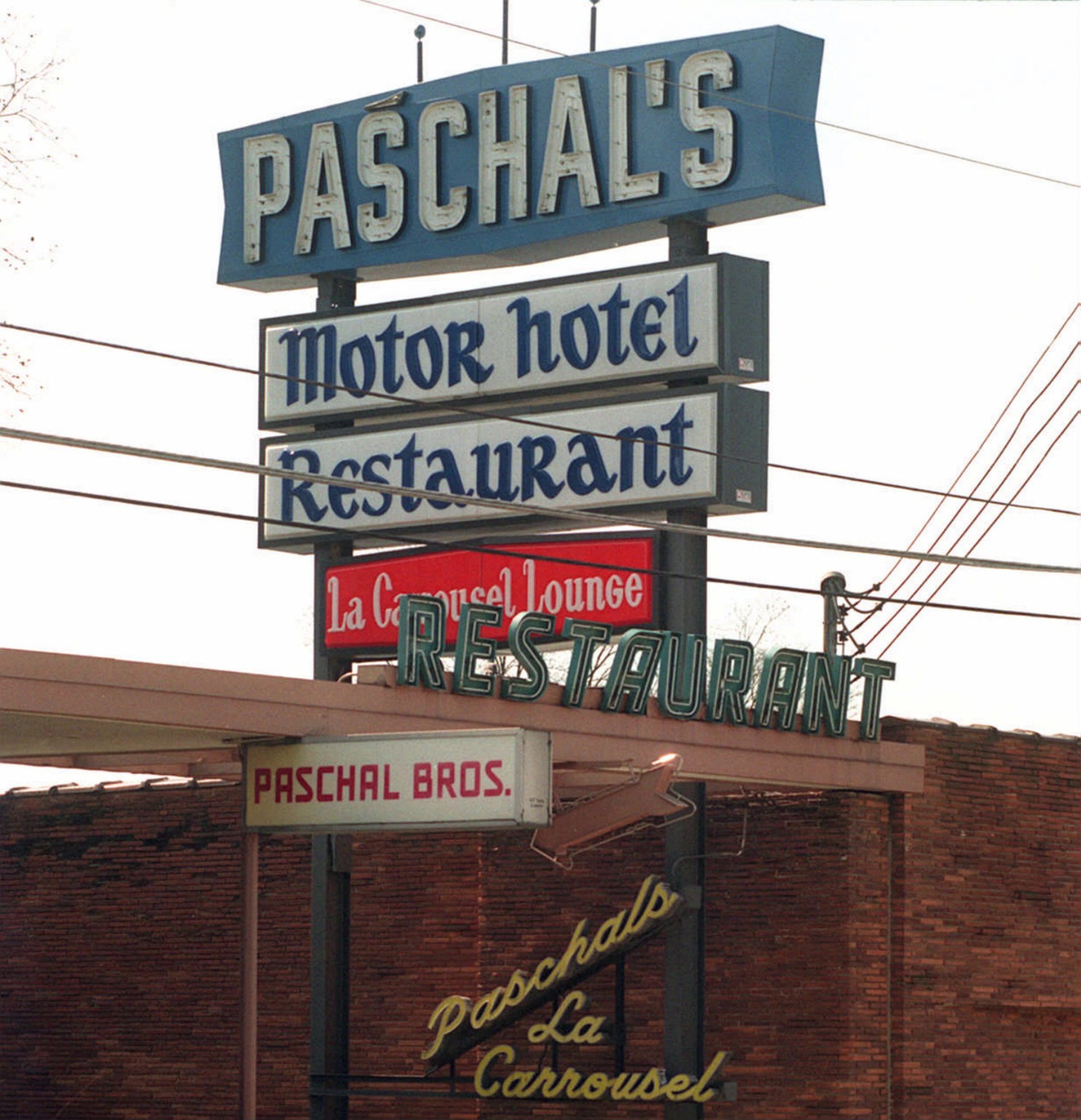

Dinner could be at Paschal’s Motor Hotel & Restaurant or Henry’s Grill & Lounge, before heading to the Top Hat Club and Royal Peacock to dance.

Even Atlanta’s HBCU’s, Spelman College, Morehouse College, Clark College, Atlanta University, Gammon Theological Institute and Morris Brown College, were listed.

“I want to demystify the myth that all Black people during segregation were poor servants,” Evans said. “I want to show vibrant families and communities who valued education and hard work. Just like every other American.”

A bygone era?

By the mid-1960s, even in the middle of the most intense period of the Civil Rights era, interest in “The Green Book” started to wane with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act.

The last edition was published in 1966.

All of the known “Green Books” have been digitized.

“I think you’re going to find a lot of reminiscing if you come with generations to this exhibit,” Evans said. “I think that moment of introducing conversation about people’s experiences is what we’re trying to provoke with this exhibit.”

Later this summer, Evans’ family will gather near Enfield for a family reunion.

Evans plans to drive.

IF YOU GO

The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum’s “The Negro Motorist Green Book”

Through June 23. The museum is also partnering with the Center for Puppetry Arts to provide public programming for educators and students, including live puppetry performances and demonstrations based on Calvin Ramsey’s “Ruth and The Green Book.” The museum will also host author lectures, family days, panel discussions and other activities throughout the run of the exhibit. 9:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Monday-Saturday. Timed tickets are $10-$12; ages 16 and younger free. 441 John Lewis Freedom Parkway NE, Atlanta. 404-865-7123, jimmycarterlibrary.gov.