Chapter 1

A Stranger in the Vestibule

On a rainy October afternoon, the old detective sits in a park near the Satilla River in southeast Georgia. He studies a sheet of paper. The page is an artifact from the case file of one of the worst things that ever happened in rural Camden County: A white man walked into a church in 1985 and fatally shot a black couple.

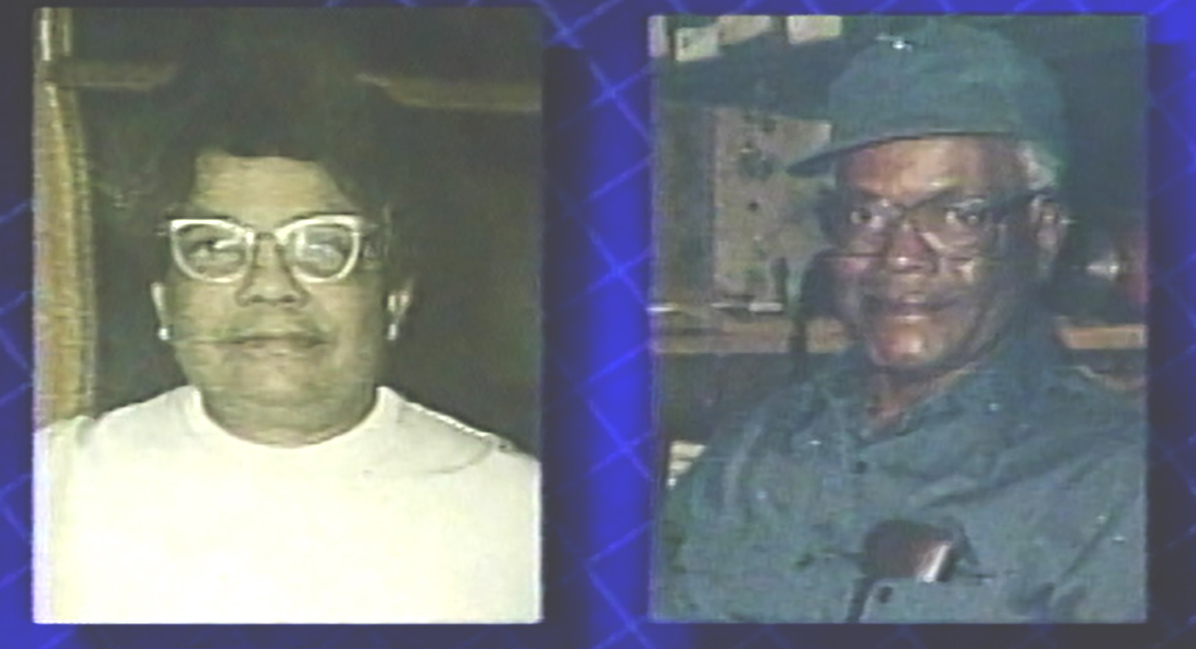

Not finding their killer is the biggest failure of Butch Kennedy’s life.

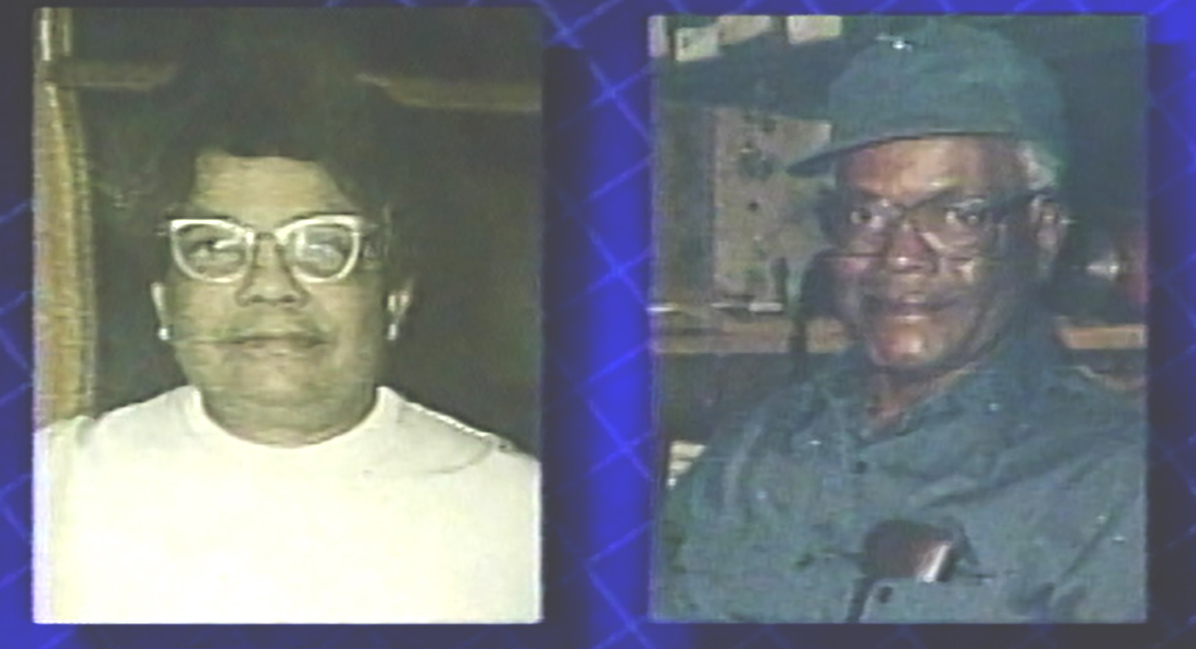

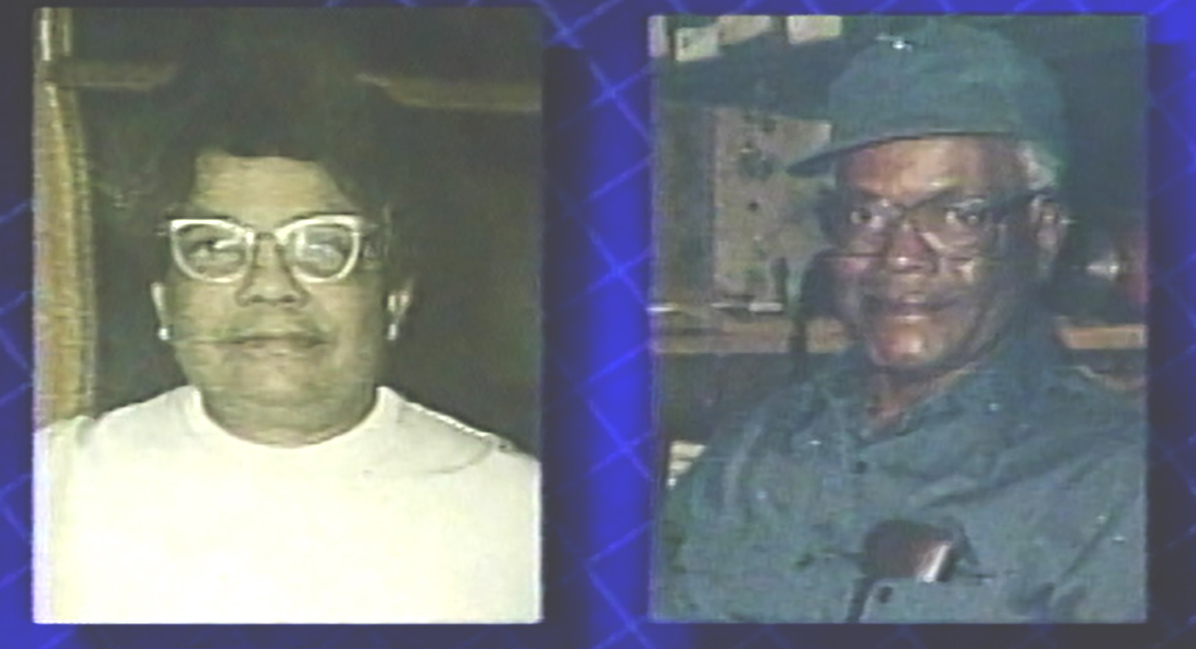

He was the chief sheriff’s deputy, and the murders were not only his to solve, but personal. He knew and respected the victims. Harold Swain, 66, was a deacon, a volunteer firefighter, the de facto spokesman for the area’s black community. Thelma Swain, 63, took the minutes at church mission meetings, doted on the couple’s adopted daughter and had a heart for people in need.

Kennedy worked to solve the couple’s murders for seven years. After he left the sheriff’s office, another detective helped convict a man who says he is innocent. Dennis Perry is serving two life sentences.

Kennedy believes the wrong man is in prison. So do at least two other investigators who worked the case. Because Kennedy was initially the lead investigator, he blames himself for how the case ended. He prays for God to show him a way to set things right.

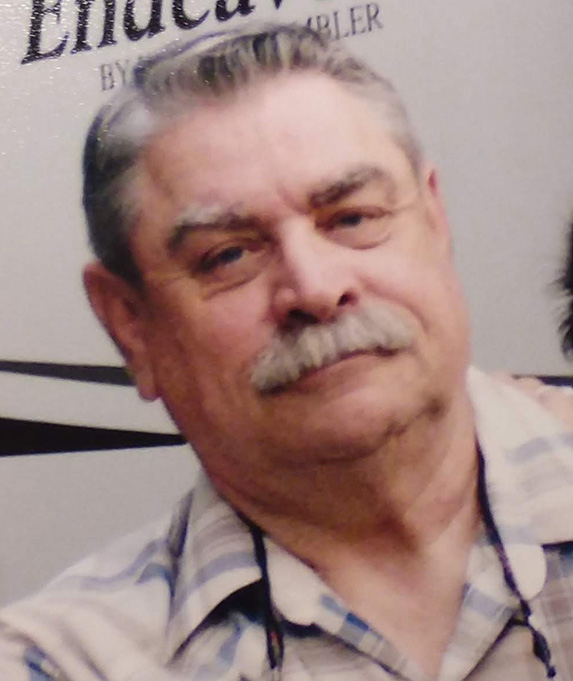

“I want to know who did this before I die,” the 74-year-old says. “You’re supposed to solve these things. You’re supposed to make them right. You feel so bad for the family. You let everybody down.”

Rain pelts the roof of the park pavilion as Kennedy examines the paper. His voice is thin and raspy, and he reads to himself in a whisper.

The sheet of paper is one I’ve chosen after reading thousands of pages of police and court documents and interviewing dozens of people over the past several months. It contains details about the alibi of a man who allegedly confessed. The alibi led Kennedy and his partner to drop the man as a suspect.

Kennedy places the paper on the table and sets his blue eyes on my face as I go line by line, telling him what I’ve learned, information that will soon change everything.

When I finish, Kennedy’s eyes get big, and he opens his mouth, but all that comes out is a loud, sickened sound: “Oh, oh, oh, oh.” The air from his lips catches the edge of the paper. The sheet lifts from the table and dances away.

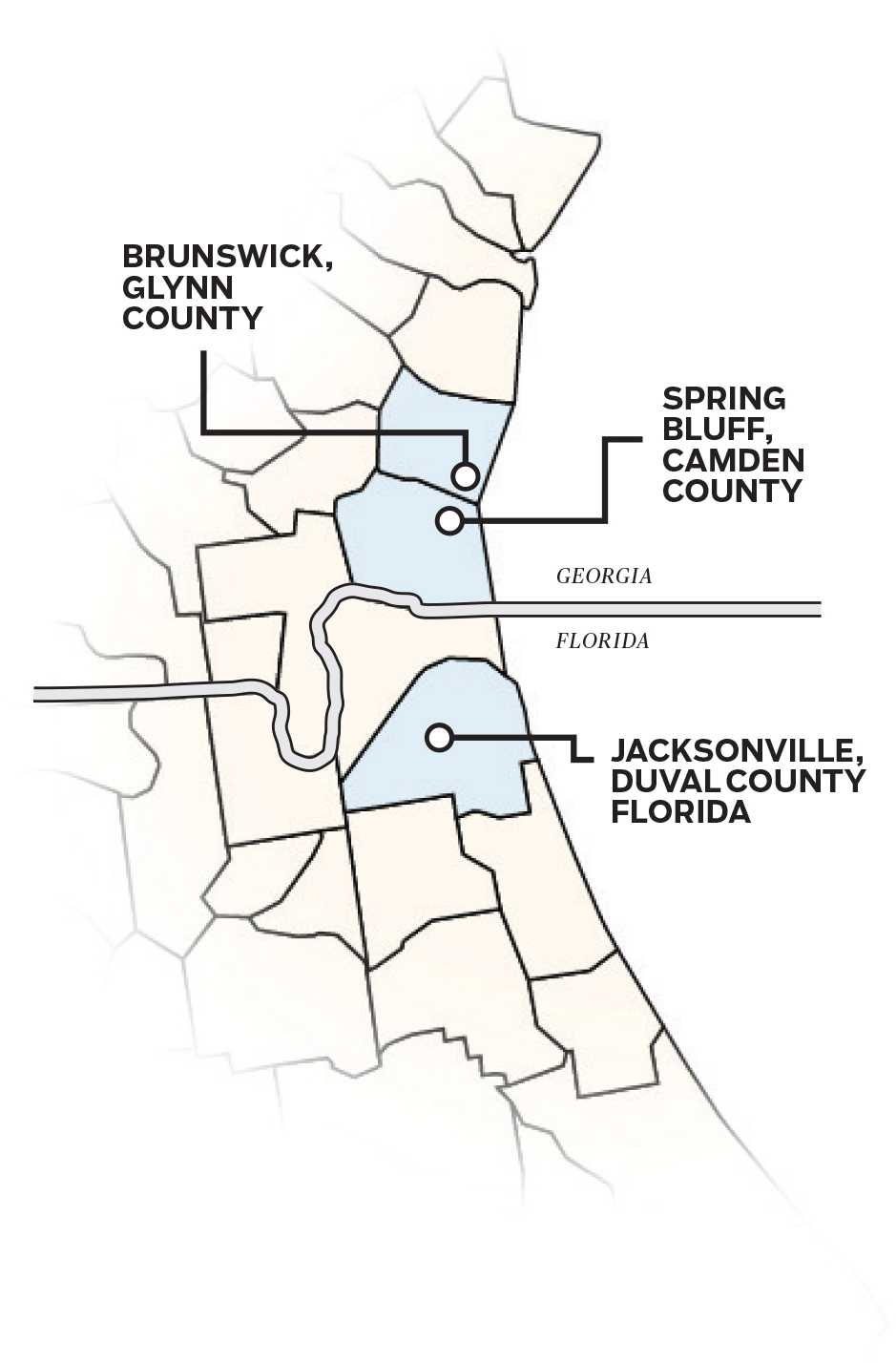

CAMDEN COUNTY IS ALMOST IN FLORIDA, almost in the Atlantic, almost swallowed by marshland teeming with fiddler crabs that perish in the beaks of whimbrels and the mouths of baby alligators that grow mighty and compete with fishermen for bigger catch. Most people live on the east side of the county, closer to the jobs at the naval base and the shrimping business around Brunswick.

If you leave the coast and drive west, passing Fancy Bluff Creek and the fast-food chains clustered around I-95, you might notice the smell of salt falling from the air, the land growing drier and harder. After 14 miles, you arrive in Spring Bluff, an area of mobile homes, aging ranch styles and piney woods.

Spring Bluff is one of those places that used to be. There used to be a place called Reed’s Store where people bought cigarettes and Cokes. There used to be a place called Choo Choo BBQ. Everybody used to know everybody.

Rising Daughter Baptist Church sits along U.S. 17, backed by woods, with a big churchyard featuring a small cemetery. It’s always been a predominantly black church, and the Swains were among its most active members.

Perry's conviction came nearly 20 years after their deaths. Last summer, the Georgia Innocence Project and the King & Spalding law firm, which took the case pro bono, filed a new petition seeking Perry's release. The filing is based largely on evidence discovered during production of the podcast "Undisclosed."

The petition accuses prosecutors of withholding information and evidence from Perry’s trial attorneys. For instance, the prosecution didn’t disclose that the star witness against Perry got a $12,000 reward for her testimony. The filing accuses the state of losing evidence that could’ve helped prove Perry’s innocence, such as documentation showing he had a strong alibi.

The court filing focuses on an alternative suspect, a former drug trafficker whom Kennedy and others long suspected of committing the murders. The podcast also focused on the former drug trafficker. Neither dug deeply into the other man who, police records say, suggested to at least two people at two different times that he committed the murders.

Realizing no one had checked into his alleged confessions and alibi since 1986, I decided to try.

What I found stunned Kennedy and his partner, as well as Perry’s attorneys and many others. Within months, the new information led to another revelation — the most dramatic development in the case’s 35-year history.

Authorities in Camden County long have said the case is over, settled, solved.

It seems they were wrong.

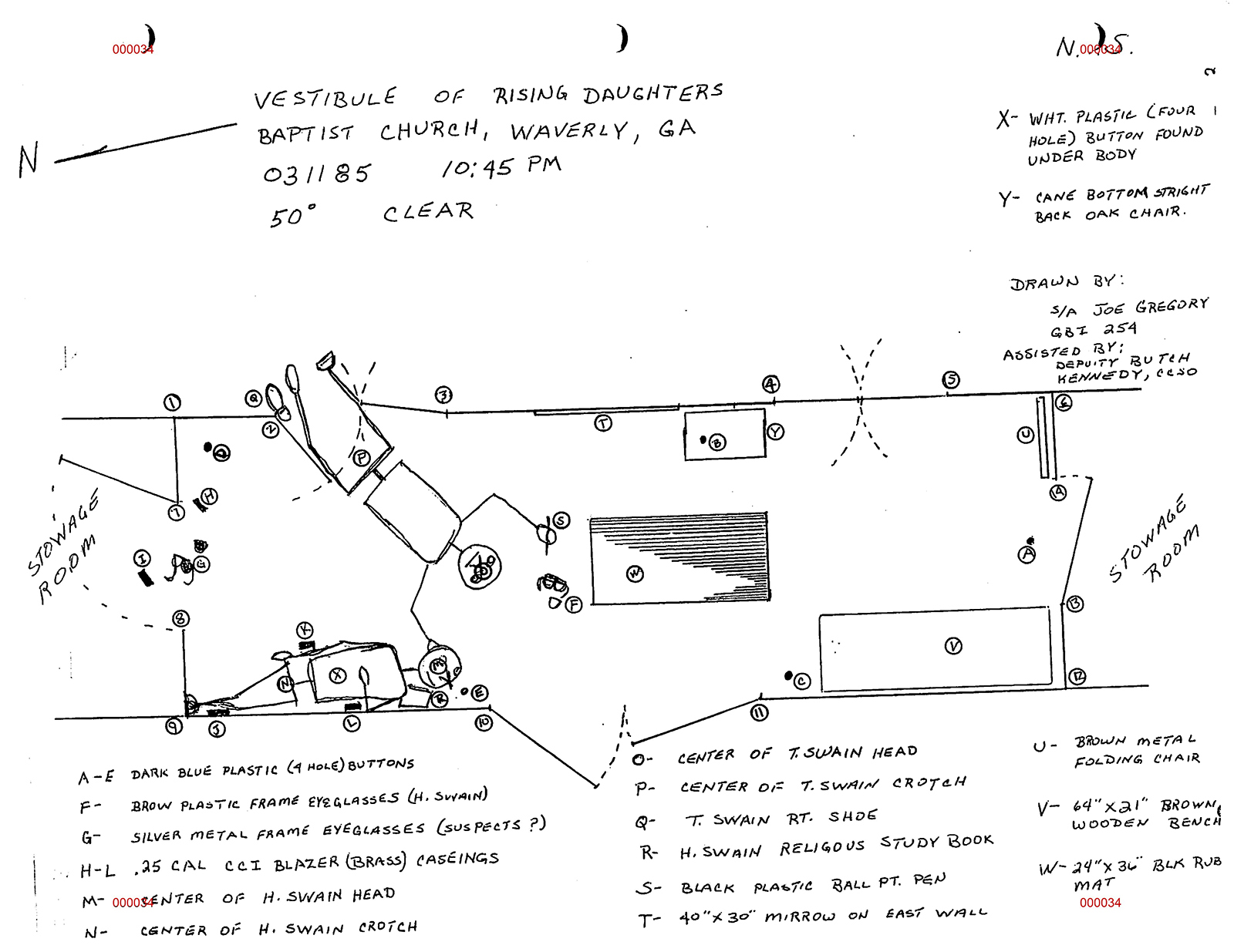

THE MOON WANED ON THAT BLACK-DARK NIGHT. As the gunman approached, a single bulb above the front door lit the churchyard in soft yellow. He might’ve heard muffled chatter about salvation as he entered the vestibule. A dozen people were in the sanctuary for a mission meeting and Bible study.

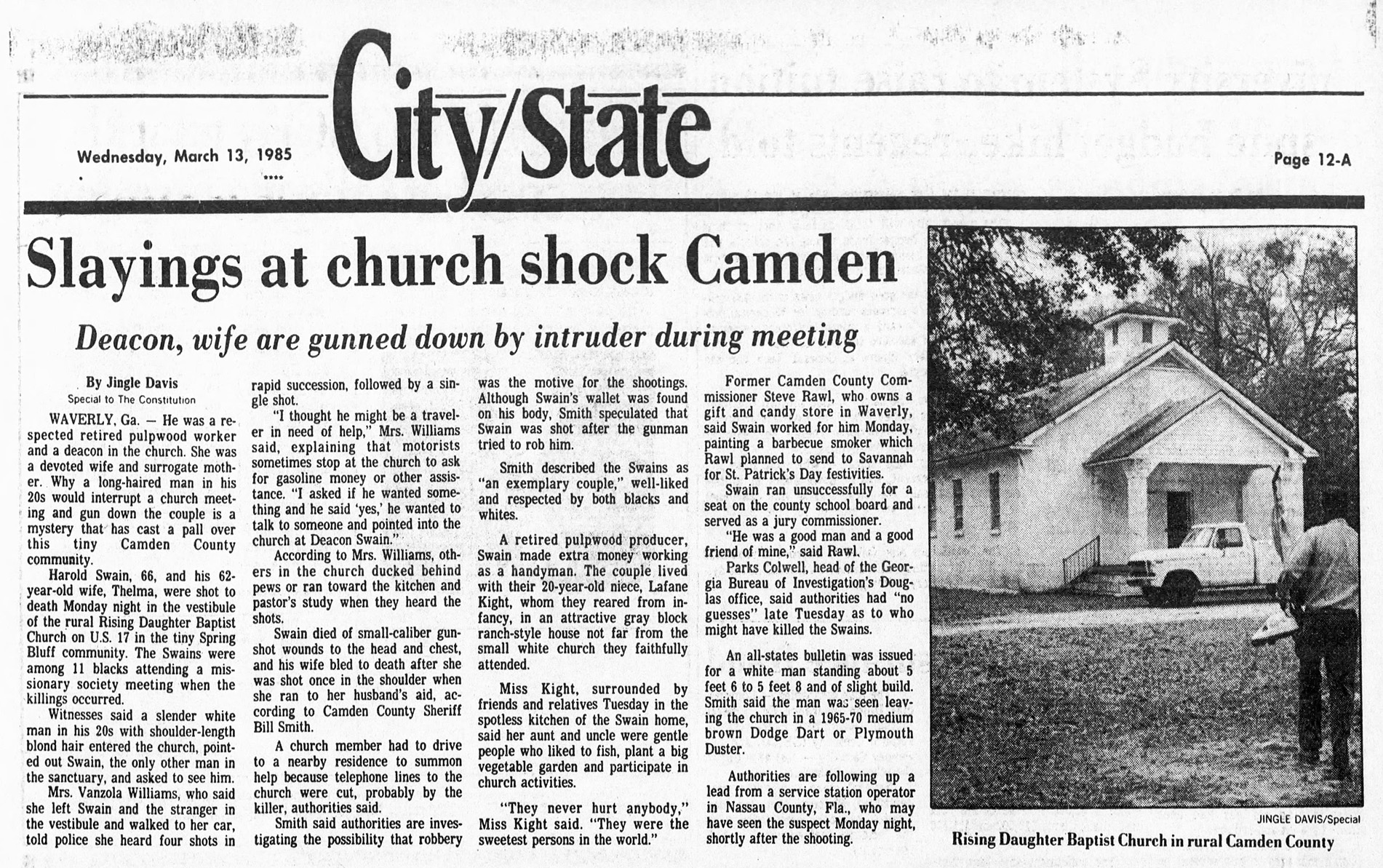

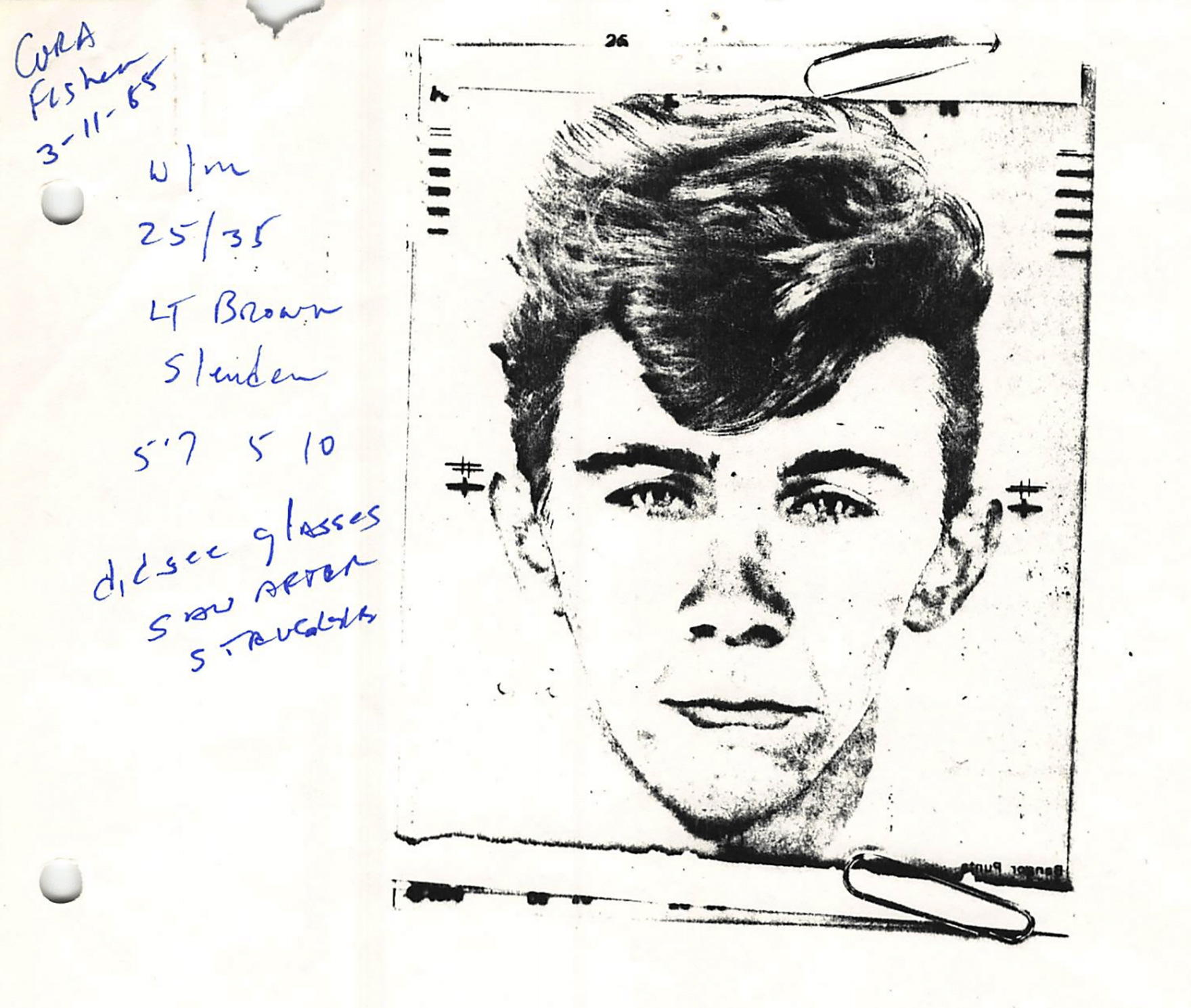

It was Monday, March 11, 1985, about 8:45 p.m. A woman who had to leave early was first to encounter the visitor, a white man who appeared to be in his 20s with light brown or dirty blond hair, collar- or shoulder-length. He said he wanted to talk to someone and pointed at the only man there.

Harold Swain, a big guy who’d been a pulpwooder, went to greet the stranger in the vestibule, a small room separated from the sanctuary by double doors.

Moments later, the women in the sanctuary heard a struggle and four gunshots. Thelma Swain ran to help her husband, who had been wounded in four places.

The visitor fired one more shot from his .25-caliber handgun, striking Thelma Swain.

One woman fainted and fell between two pews. The others, including a 7-year-old girl, scrambled out of the sanctuary and into the kitchen or the pastor’s study. Someone tried to use the phone to call for help, but the line was dead. The Lord knows how long they waited in silence, praying, before Marjorie Moore got a burst of courage.

First she needed a weapon.

She grabbed a broom.

Then she ran outside, where she noticed an unfamiliar car, brownish and sporty, parked at the edge of the yard. Maybe the shooter was inside reloading, she thought. She dropped the broom, jumped into her car and sped toward the convenience store down the road.

A clerk called police while the owner drove Moore back to the church. The car she’d seen was gone.

So was the killer.

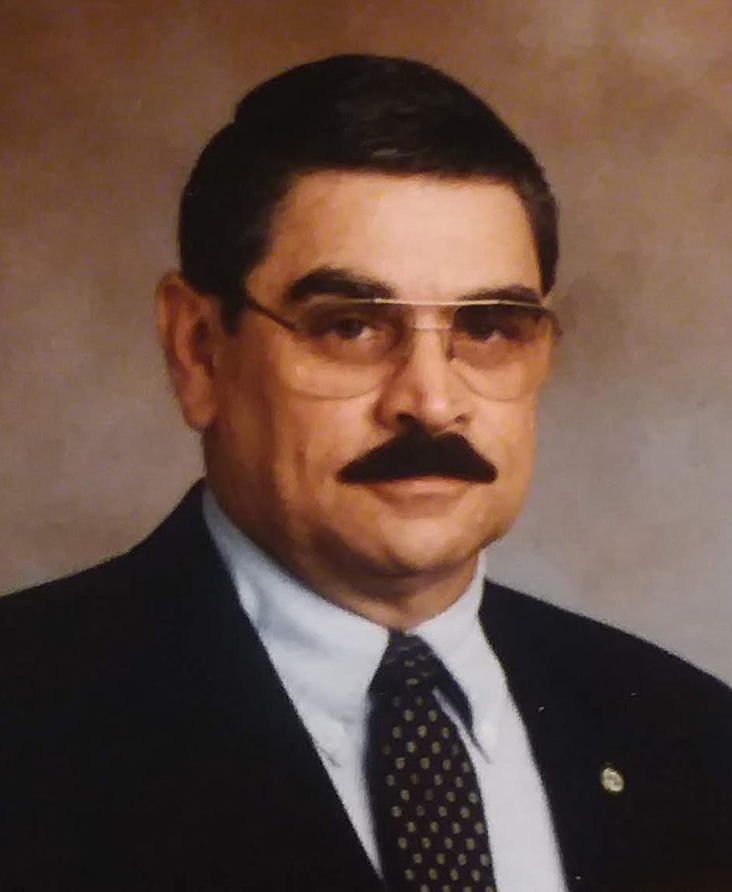

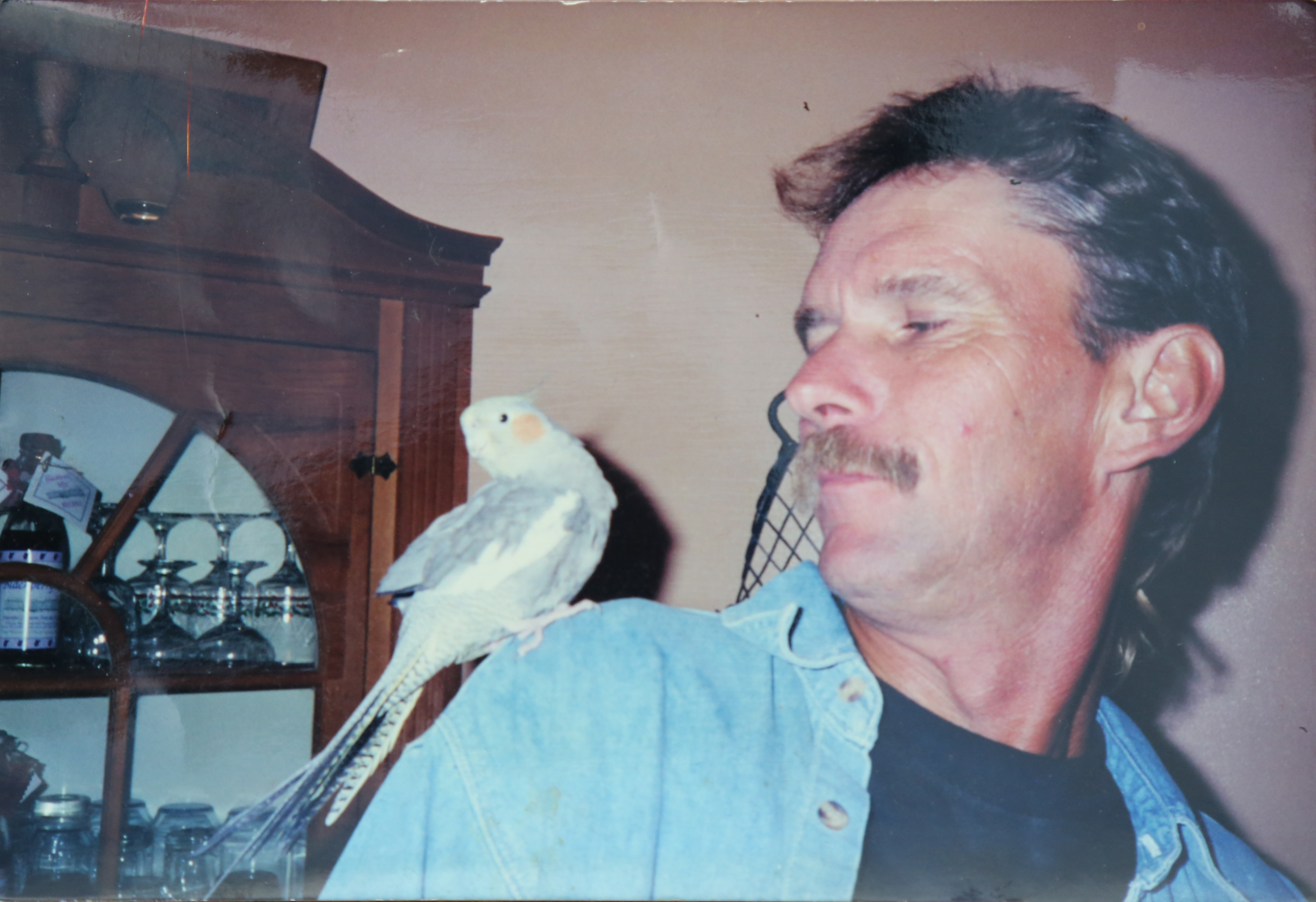

BUTCH KENNEDY, A VIETNAM VET, was 40 at the time and had become a deputy because his dad was a deputy. He was chief deputy, as his dad had been in Telfair County, where Kennedy grew up in an employee suite under the second-floor jail.

Between his eyes, he had a scar from when a suspect smashed a beer bottle on his face. In the pants pocket of his uniform, he carried a silver coin embossed with the outline of a fish, a symbol for Jesus.

Kennedy felt a man was only as good as the way he served others. Typically, he thought he was pretty good. He’d worked a few homicides before. But when he arrived at the church, he felt a pounding fear of failure.

The scene was surreal, shocking. The Swains lay faceup, side by side, soaked in blood. Thelma’s left hand touched the back of her husband’s head, like she was comforting him.

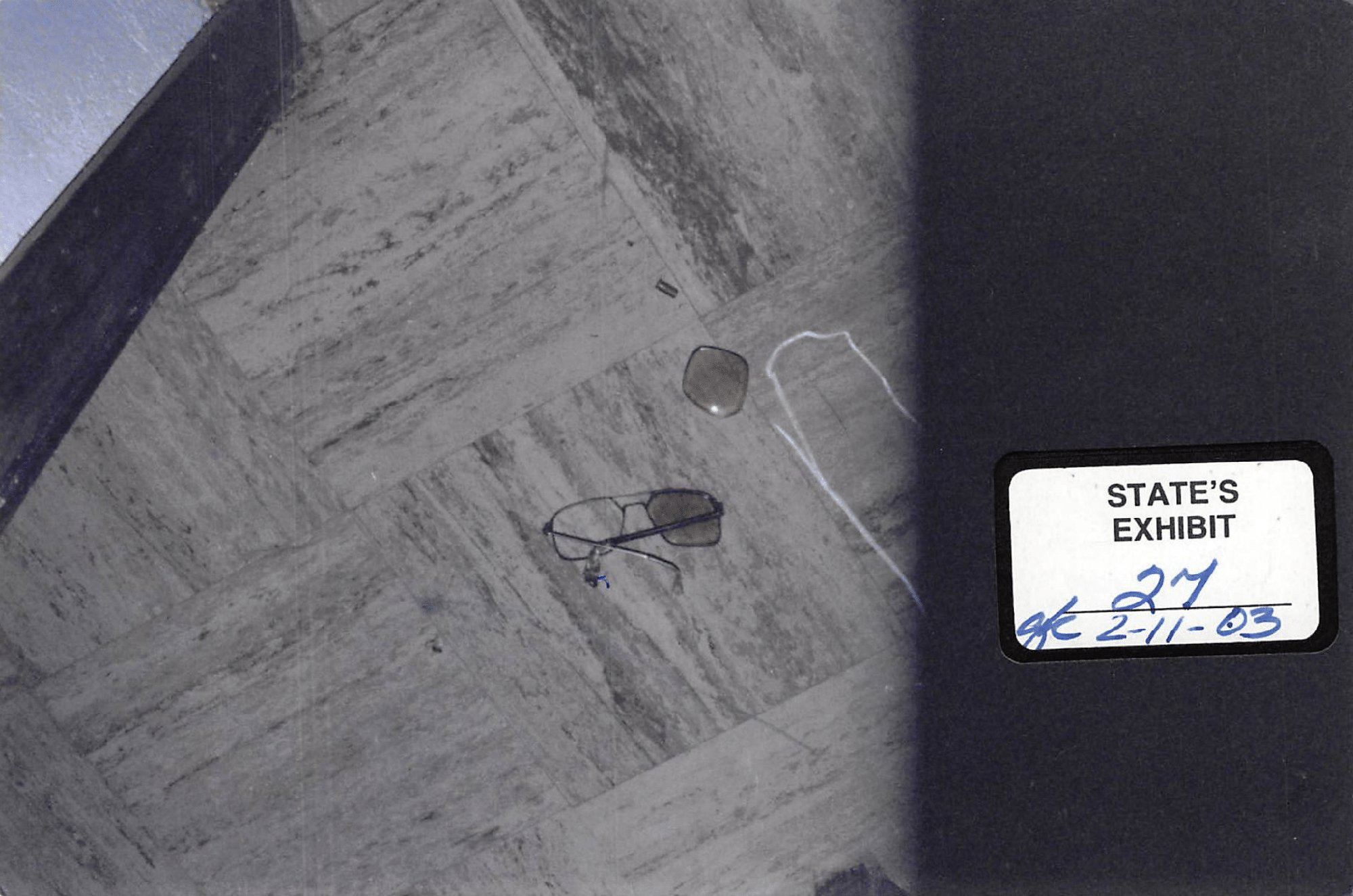

Kennedy’s partner in the investigation was a sharp-tongued GBI agent and fellow Vietnam veteran named Joe Gregory. When he arrived, Kennedy took him to the bodies. They noticed a pair of glasses, inches from the Swains.

None of the church witnesses knew whose they were. They didn’t agree on whether the killer had been wearing glasses. But here was a pair. They were distinctive, too: thick lenses, pitted and worn, with residue of transmission fluid on them. The temple pieces didn’t match. Whether they’d fallen off his face or from his pocket, the killer must’ve dropped them, the detectives agreed.

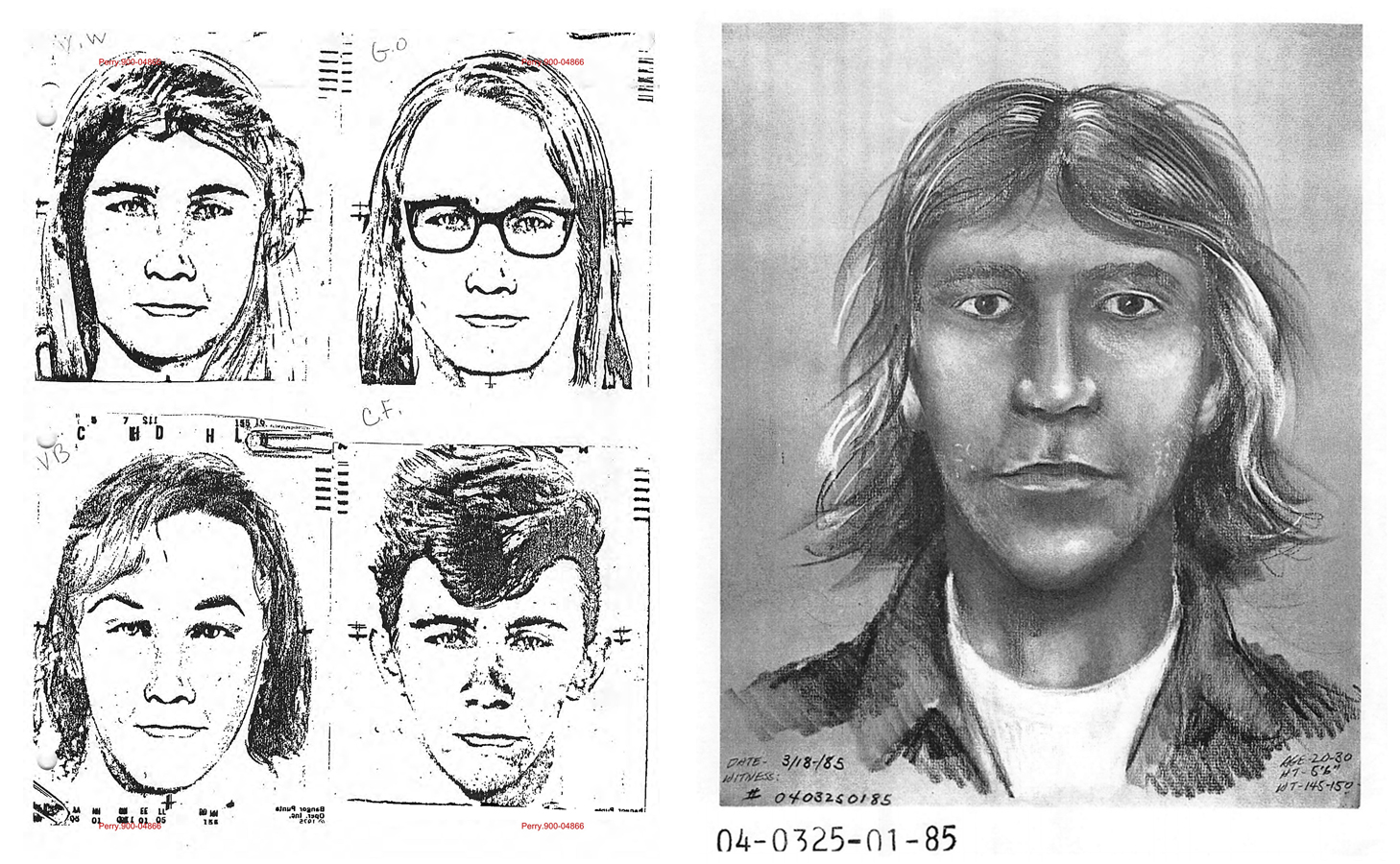

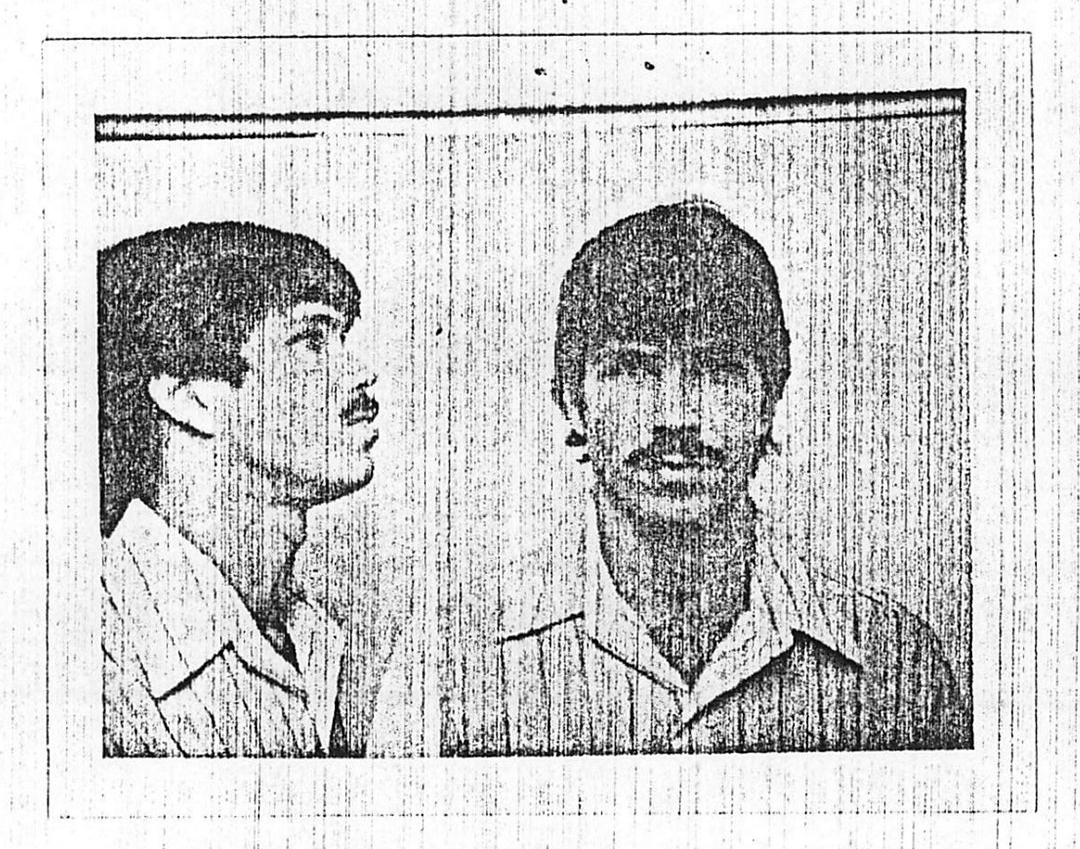

A few days later, the sheriff’s office brought in a sketch artist who sat down with four witnesses from the church who said they had seen the gunman’s face. Each woman’s memory produced a sketch, and afterward the artist combined all four into a composite drawing. The artist told Kennedy the witnesses were generally happy with the composite because it captured some of what they all remembered. But one woman didn’t think it looked like the killer. Still, it appeared in newspapers, on TV and on the walls of gas stations.

The detectives were bombarded with leads. Men who wore glasses held special interest. Kennedy and Gregory checked their prescriptions against the glasses found at the scene. None ever matched.

Motive was elusive, too.

A grudge against Harold Swain? Who didn’t like the man who helped neighbors with yardwork and waved when you passed him on the road? Plus, witnesses said Harold didn’t appear to know the intruder.

Racism? That seemed unlikely to many locals, considering how beloved the Swains were among both black and white residents.

Robbery? Harold still had $300 in the pocket of his blue jeans when authorities arrived. Had the gunman gone to the church to rob congregants and aborted the plan when Harold resisted?

The detectives soon would come to believe that Harold was the target of a hit job.

THE DETECTIVES PRAYED in their windowless office. They prayed driving to interrogations. They prayed when they woke in the morning and placed their feet on the ground.

Gregory was a faithful man. Kennedy didn’t believe prayer worked, but he grew up Baptist and learned that praying is what you do when you feel helpless.

Kennedy thought often of the crime scene. He could remember how the sanctuary smelled of the women’s perfume. He couldn’t stop seeing Harold and Thelma’s bodies on the gray tile floor.

Sometimes the detective drove to the church and looked around, thinking. One day he parked the car in the yard and started to cry. He climbed out and paced in the grass, trying to compose himself so he could get back to work.

IN JULY, FOUR MONTHS AFTER THE CRIME, Kennedy and Gregory arrived at the Telfair County jail to talk with an inmate who said he had information about the murders.

The man had been arrested with two buddies after a state trooper found a machine gun in the trunk of their car. Police said the men were tied to a drug-trafficking operation.

The inmate told detectives that not long after the murders, he’d had a party at his house in the Florida Panhandle. Donnie Barrentine, who was in the jail with him on the machine gun charge, had drunkenly waved around a 9 mm handgun, the inmate said, and claimed to be God.

God can give and God can take away, the inmate remembered him saying. Then Barrentine said he’d taken something, according to the inmate: the lives of two black people in a church.

The inmate, who spoke with the investigators multiple times, said Barrentine later told him why he killed the couple: The Swains’ son-in-law owed money to a drug trafficker. The hit was supposed to bring the son-in-law out of hiding. Or something like that. The story changed as the inmate said he talked further with Barrentine at the jail.

But in the shifting words, Kennedy thought he heard some truth.

The Swains had no son-in-law, but their adopted daughter’s stepfather was under federal indictment — and soon to be convicted — for importing marijuana from Jamaica. The feds had hidden him out once when he turned government witness. (The stepfather died in 2014; the Swains’ daughter, who was 20 when they were murdered, couldn’t be reached for comment.)

Kennedy and Gregory found other witnesses who said they heard Barrentine talk about the murders at the party. They also checked out his alibi — he’d been working 245 miles away in Marianna, Florida, on the day of the shooting — but the detectives drove the distance and believed he could’ve made it to the church in time to commit the murders. It wasn’t clear whether Barrentine had access to a car like the one seen at the church.

His shoulder-length brown hair matched the description of the gunman. But he maintained his innocence, and the district attorney said the investigators needed more to charge him.

As months slid by without an arrest, Kennedy says, his boss pressured him: Where are you on the Swain case? I’m going to have to replace you.

Though the sheriff’s words stung, nothing could hurt more than Kennedy’s thoughts about himself. Privately, Kennedy wondered if the biggest problem with the Swain case was him.

Chapter 2

The Glasses and a Confession

Kennedy didn’t like to be too seduced by any one theory. But he felt attracted to the inmate’s story about Barrentine. Feuding drug traffickers in southeast Georgia. An attack on a snitch’s kin because he was in the witness protection program. A man claiming to be God murdering people in a house of God. And others had corroborated what the inmate said: that Barrentine boasted about committing the murders.

But then Kennedy heard a new story about another man.

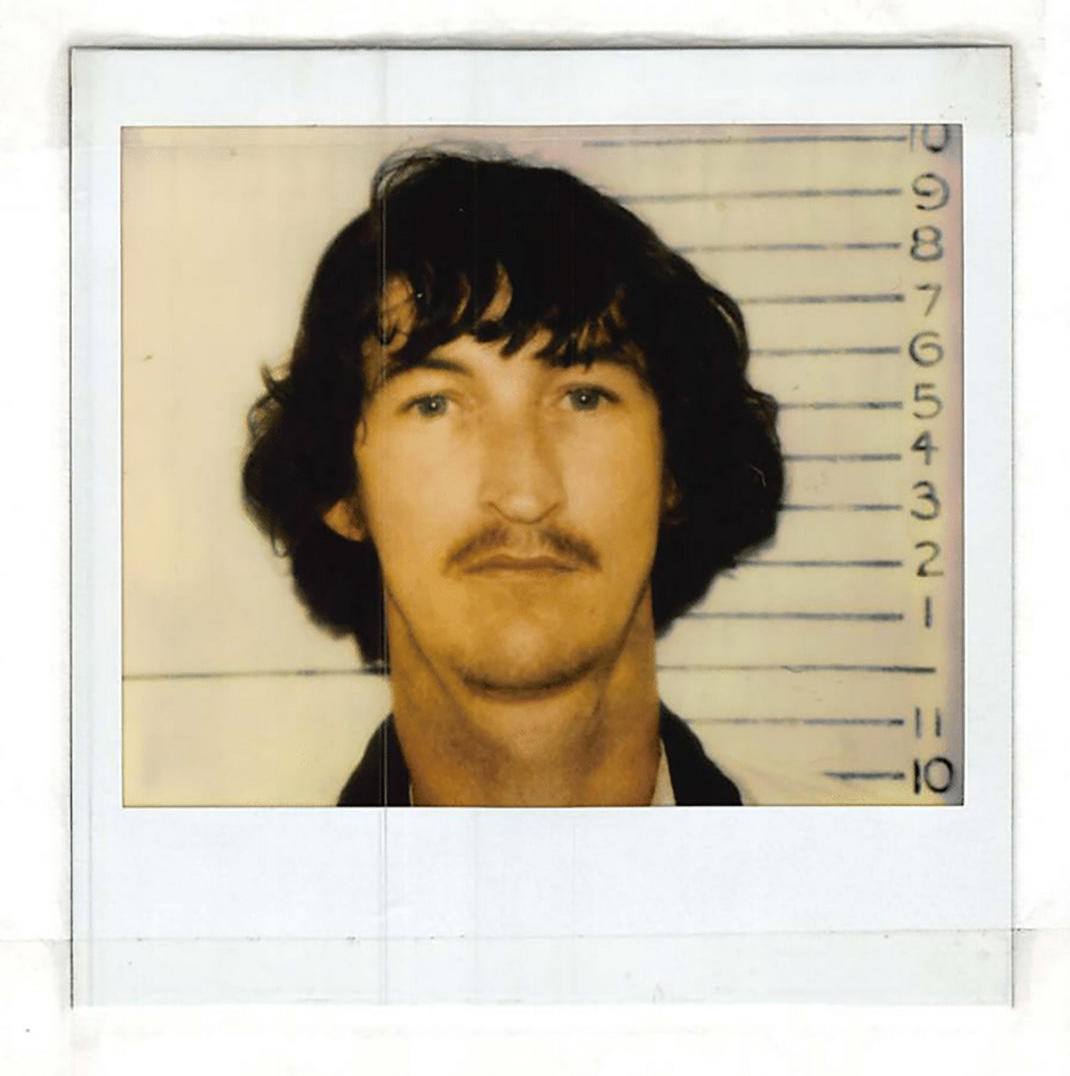

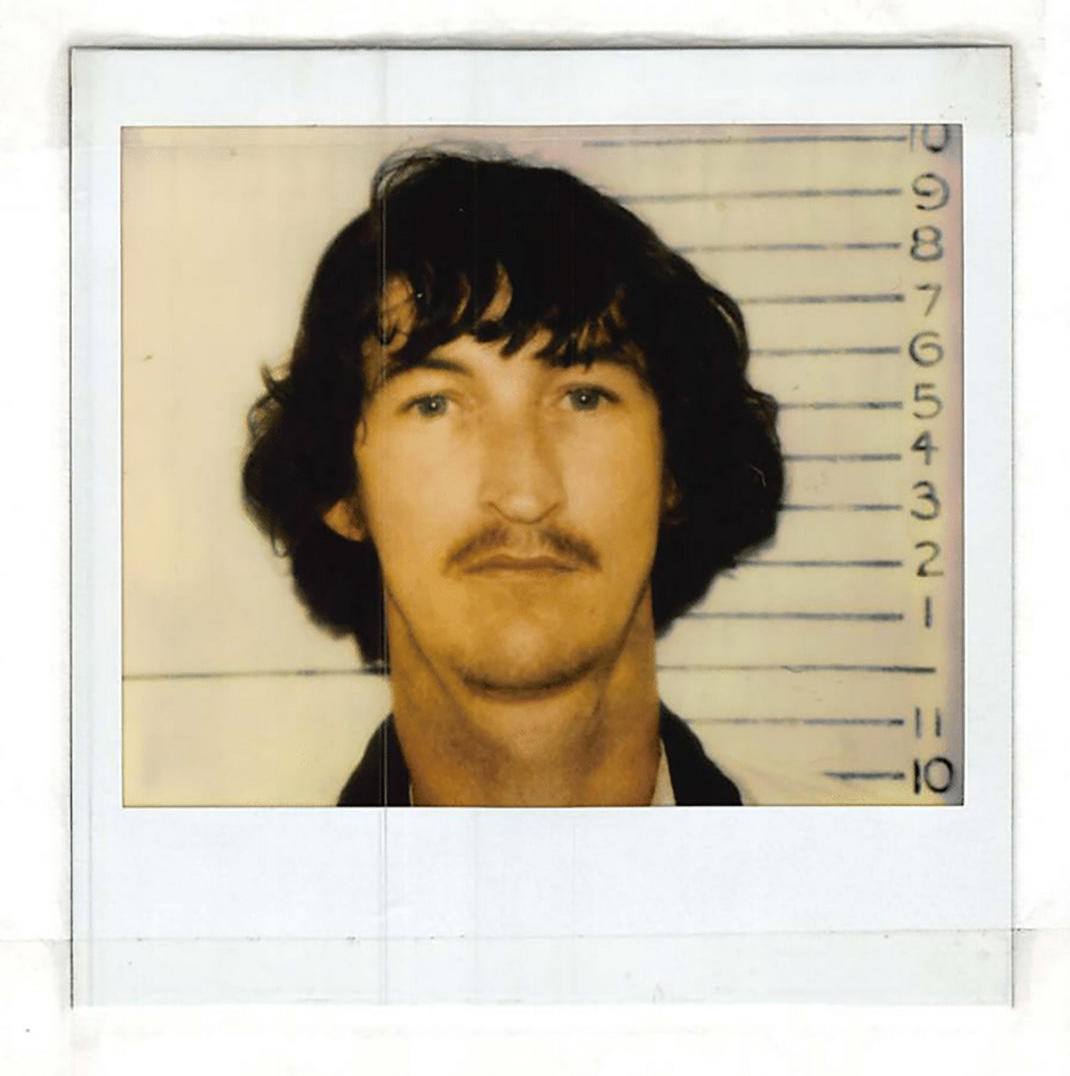

Erik Sparre grew up in Brunswick, but he’d spent a lot of time around Spring Bluff. Kennedy thought of him as a hellion. He had allegedly pulled a rifle on a black or Asian man at Choo Choo BBQ and kicked the windshield out of his car, according to a police document. During a DUI arrest, he threatened to bloody a Glynn County police officer who he called a “n----- loving whore,” though the report says he wasn’t charged with the threat. Kennedy had arrested Sparre for allegedly beating his first wife, Emily Head Sparre, before she said to drop the charges.

In March 1986, about a year after the Swains’ murders, Emily was no longer married to Sparre, and Kennedy learned Sparre had been harassing and threatening her family.

While Sparre was on the phone with Emily’s twin brother, the family recorded the call. They let Kennedy hear it, according to a report.

“I’m the motherf----- that killed the two n------ in that church,” the document quotes the caller saying, “and I’m going to kill you and the whole damn family if I have to do it in church.”

The family said the voice was Sparre’s.

Kennedy spoke with Emily at her parents’ home in Spring Bluff.

Emily, who said Sparre hated black people, recalled him leaving home one morning wearing dark clothing. The next morning, he returned wearing a white shirt. She said this was during the week of the murders, and she left him a week later.

Kennedy knew the killer had worn dark clothes, including a shirt that lost a couple of buttons in the struggle with Harold Swain. Sparre also had collar-length brown hair.

And what about the glasses found at the crime scene?

Emily said Sparre had lost his glasses sometime before the murders. “He got three pairs of glasses from his father,” Kennedy later wrote in a document. “Erik Sparre made one pair of glasses out of the three pairs. ... She stated that he is a welder and had worked for a trucking service as a mechanic.”

Kennedy knew this could explain the condition of the glasses: the marks on the lenses, the transmission fluid, the mismatched temple pieces.

He got in his cruiser and drove toward the sheriff’s office. On U.S. 17, he passed Rising Daughter on his left. Whenever he went by the church, he said a prayer for God to help him solve the case. Was God delivering now?

At the sheriff’s office, Kennedy grabbed the glasses from the scene and two unrelated pairs. The detectives had so far kept information about the glasses close to the vest.

Back at Emily’s parents’ house, Kennedy asked if any of the three pairs looked like Sparre’s.

Emily picked the pair found near the bodies.

WITHIN HOURS, KENNEDY SOUGHT A WARRANT to search the house where Erik Sparre lived with his parents in Brunswick. At 4:30 p.m. on March 10, 1986, one day before the first anniversary of the murders, he and Gregory entered the home looking for a handgun like the killer used, and anything else that might link Sparre to the crime.

They found nothing.

The detectives were unable to link Sparre to a car like the one at the crime scene. They needed to know if he had an alibi.

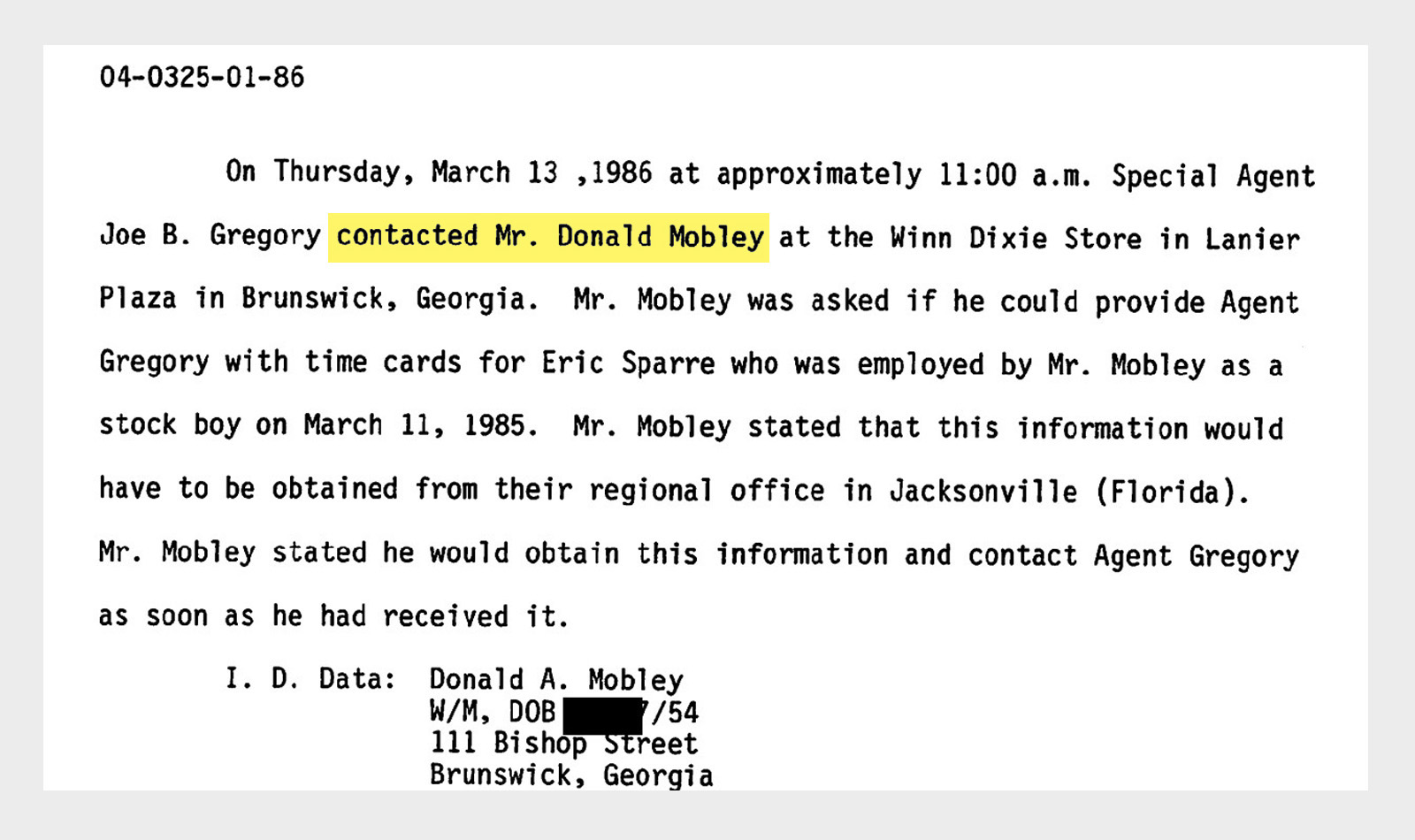

Gregory got a number for the manager at the Winn-Dixie where Sparre was said to have worked at the time of the murders. Was Sparre on the job that night, Gregory asked. The manager, who identified himself as Donald A. Mobley, said he’d have to check with headquarters. It’d been a whole year.

Two weeks later, Gregory’s phone rang. It was a man who said he was Mobley. He said Sparre clocked in at 3:06 p.m. on the day of the murders and clocked out the next morning at 6:41 a.m.

“I have also talked with employees who are still working here who worked with Sparre that night,” Gregory quoted Mobley as saying in the report. “They also confirmed that Sparre was in the store on that evening.”

Gregory didn’t meet Mobley in person, but the call was good enough for him and Kennedy. Sparre’s alibi had checked out. The investigators wrote him off as a suspect. His name never came up in their files again.

A YEAR TURNED TO TWO, THEN THREE, and the detectives felt discouraged. Having leads that went nowhere felt bad, but having no leads at all felt worse.

They were grateful even for tips they found flimsy.

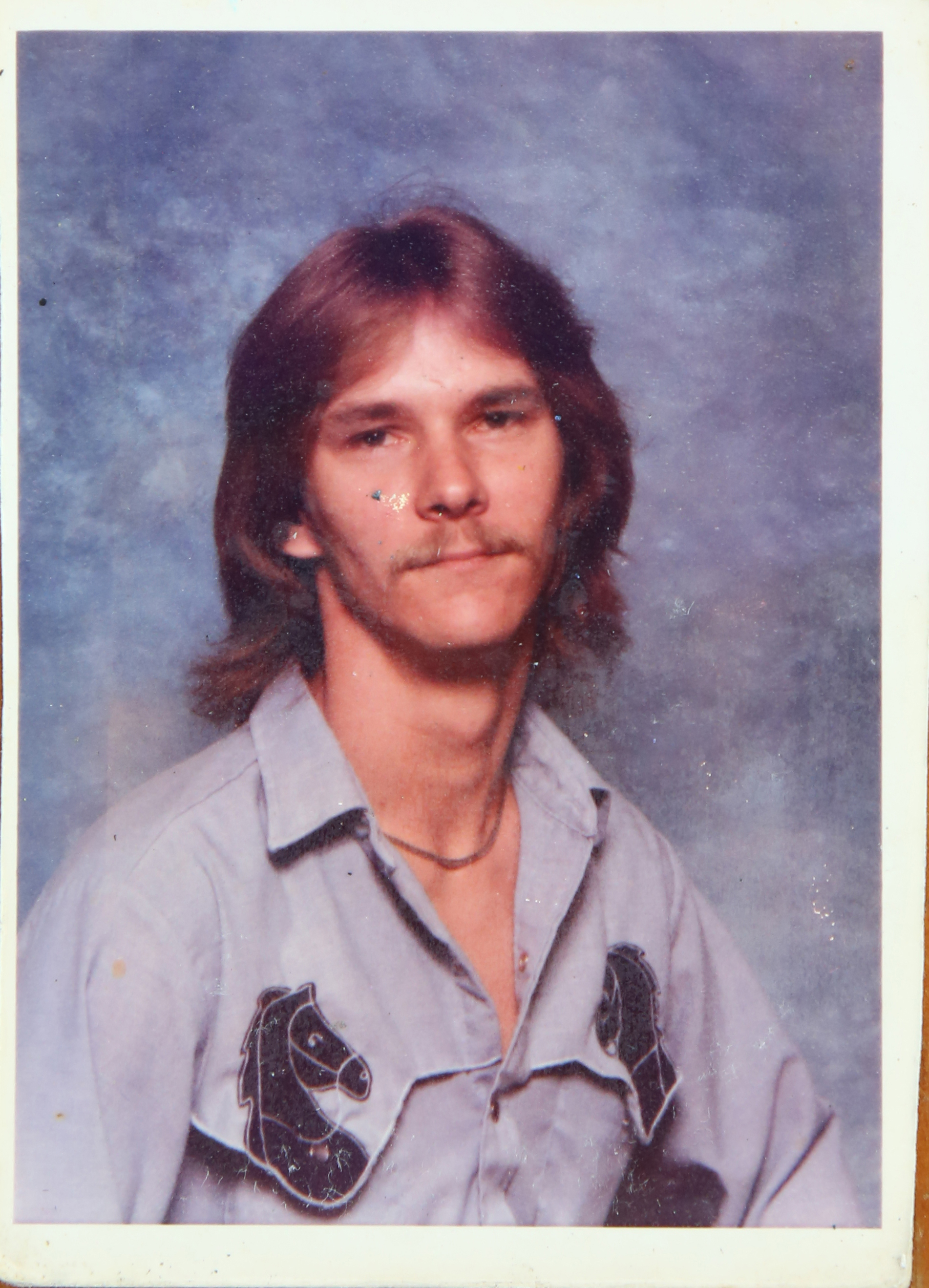

One such tip produced the name of Dennis Perry.

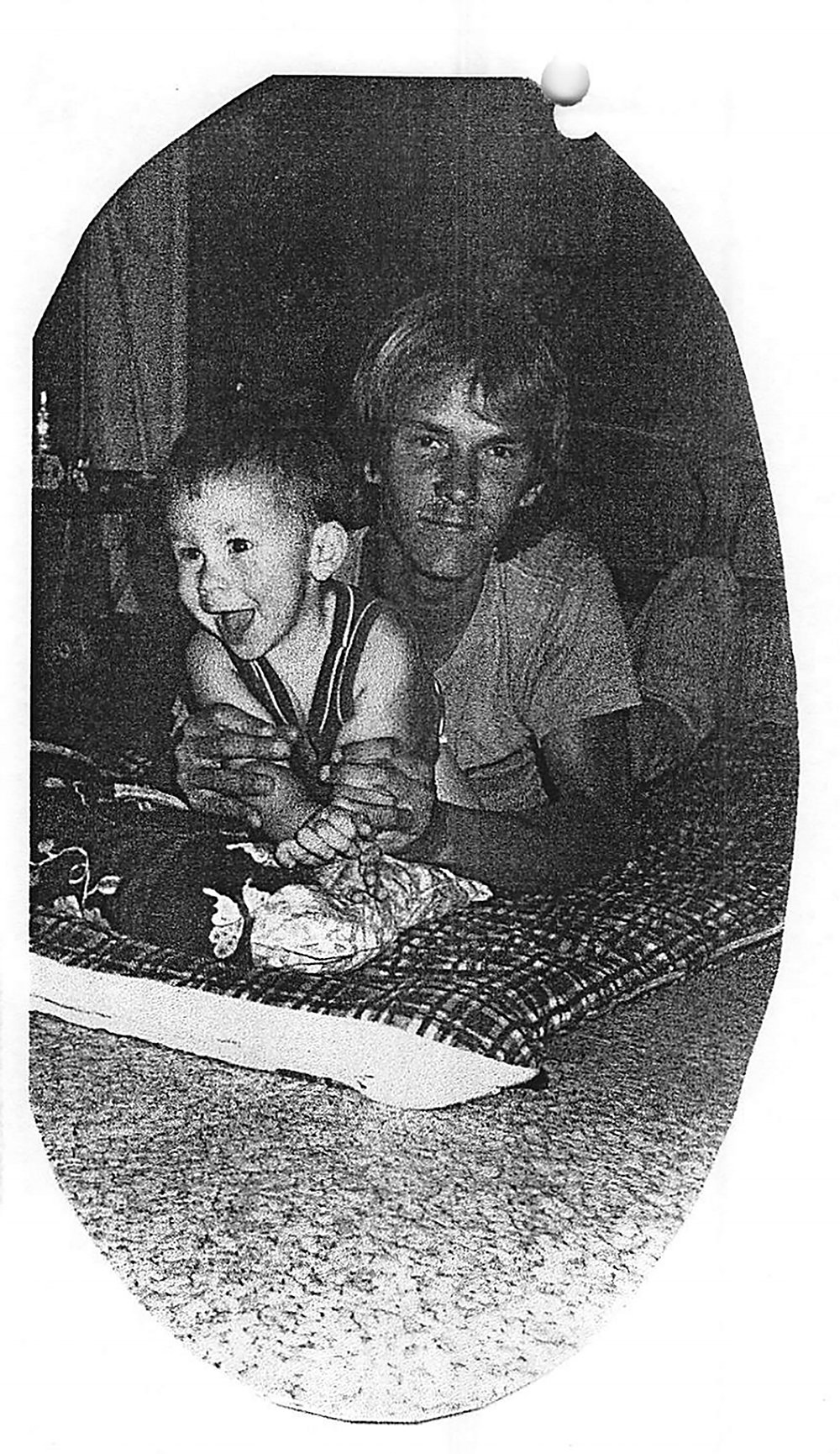

Perry was 26, a long-haired country guy who liked to fish and deer hunt. He had lived for a time in Spring Bluff. His grandfather had a chronic condition, and Perry helped care for him at his grandparents’ home on Dover Bluff Road near Rising Daughter Baptist Church.

Four months before the murders, Perry had fallen out of a tree stand while deer hunting and fractured a vertebra. His mom had taken him to her house in Jonesboro, near Atlanta, to recuperate.

Kennedy had never heard of Perry until the tipster called to allege Perry had a problem with Harold Swain. The detectives found no evidence to support the story. They also learned Perry had no car and didn’t wear glasses.

They still wanted to see if he had an alibi. They talked to Perry’s family and learned he worked at a concrete company in College Park at the time of the murders. Gregory says the boss confirmed Perry had worked that day, late into the afternoon. Kennedy and Gregory believed Perry wouldn’t have had enough time to drive the 260-odd miles and make it to Rising Daughter at 8:45 p.m.

Even so, Kennedy and Gregory put together a photo spread with the faces of Perry and five other men. They showed it to the woman who had spoken with the gunman in the church. She didn’t recognize anyone.

THE CHURCH MURDERS GAINED NATIONAL ATTENTION in November 1988 with a segment on TV’s “Unsolved Mysteries.” “The quiet sanctity of Rising Daughter Church was violated by the brutal double murder,” said the velvet voice of the show’s host.

Kennedy and Gregory took part in the filming, doing reenactments of the crime scene and the investigation. Gregory said on the show that the glasses from the church must’ve belonged to the killer.

During the debut broadcast, the detectives were horrified to see the show’s host holding the glasses with his bare hands. They hadn’t realized someone sent physical evidence to the producers.

Minutes after the show concluded, tips flooded in from all over the country.

The detectives spent long days chasing dead-end leads. And on some nights, Kennedy stopped to buy a six-pack of Bud Light on the way home. The chief deputy knew he couldn’t get drunk in case he had to go out on a call. He sat on his porch alone and drank just a can or two, enough to feel a little lighter, light enough to keep going. He stared out into the dark in silence.

Chapter 3

Convicted by ‘The Bundy Method’

In the summer of 1992, Butch Kennedy cleaned out his office and walked away with a terrible feeling: He would never be a cop again.

Kennedy says Sheriff Bill Smith fired him. Smith has said Kennedy resigned. Either way, the job that gave Kennedy purpose was gone.

He took a job as a tax collector. He thought every day of how he’d failed in the Swain case, how he’d failed as a deputy. He figured he’d fail at the new job, too. After eight solid years of unanswered prayers, he learned drinking is something you can do when you feel helpless. So he drank.

Alcohol didn’t consume his life, but it dulled the regret and disappointment that never left his mind.

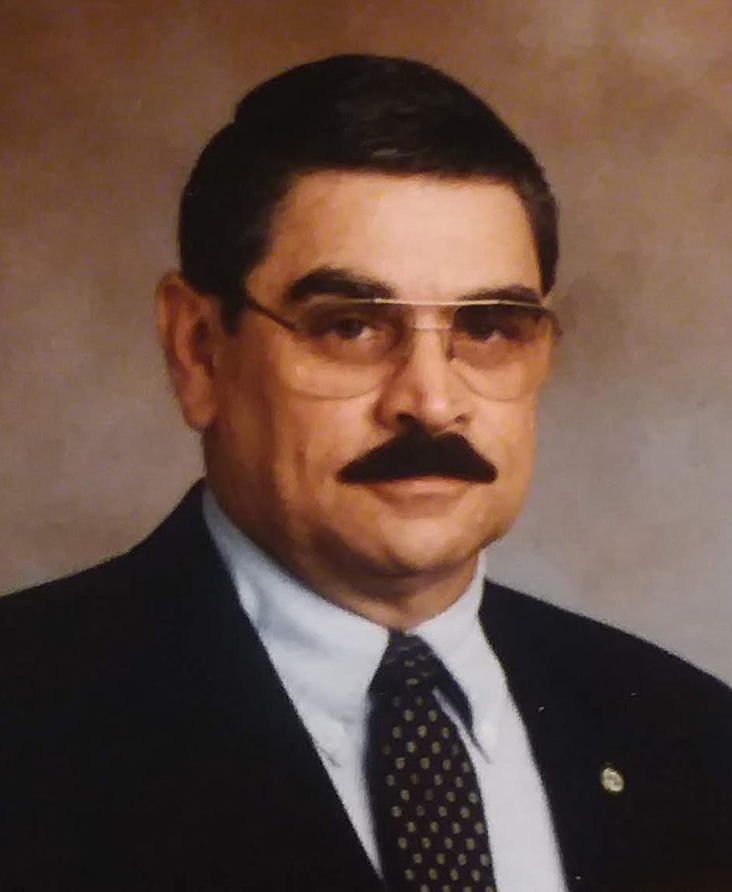

Six years later, the sheriff rehired a former deputy, Dale Bundy, to work the murder case. (Smith, who is no longer sheriff, declined to comment.) The sheriff gave him a one-year contract, with no guarantee of renewal, to work exclusively on the Swain murders, which had confounded investigators for 13 years. Gregory, who was still the GBI’s lead on the case, had recently broken his back and neck in a car wreck. Bundy, 50, would do the job alone.

Bundy declined the AJC’s requests for an interview, saying he’d been treated unfairly by the Georgia Innocence Project as it fought Perry’s conviction. But I obtained his more than two-hour interview with the podcast “Undisclosed.”

“I’ve been made to look like just a horrible person that framed this poor innocent man,” Bundy said. “I put a lot of my time in this case — I was very careful with it. The last thing I’d want to do is to put someone in prison that I didn’t think was guilty.”

The unedited tape of that interview, as well as Bundy’s trial testimony, details how he built the case against Perry.

He started by re-interviewing the church witnesses.

Had they heard anything new in the last 13 years?

CORA FISHER SAT WITH BUNDY on her screened-in porch days after he began work. She was the church member who had fainted when the gunman fired. But the 66-year-old had always said she got a good look at his face.

Cora, Bundy asked, do you think you know who killed Harold and Thelma Swain?

I don’t think anything, Cora said. I know who killed Harold and Thelma Swain.

Fisher told Bundy she’d learned who the killer was in 1988. Shortly after “Unsolved Mysteries” aired, a white woman came to her home and showed her a photograph of a man and asked whether he was the gunman.

Fisher took one look and fainted.

Yes, that was the man.

Fisher was too scared to give the killer’s name to Bundy. But she offered a hint: The man’s grandfather used to live in a white house on Dover Bluff Road.

Bundy realized she was talking about Dennis Perry.

It’s unclear whether Bundy knew Kennedy and Gregory had cleared Perry 10 years earlier. Nearly all documentation from their efforts to investigate Perry is gone from the case file, though no one can — or will — explain why.

Bundy told “Undisclosed” he didn’t record interviews, and he testified that he took no notes in his investigation. Instead, he said he remembered what people told him and sat down once he’d completed most interviews and wrote a case report. He wrote the report on this case five months after the first interview with Fisher.

THREE WEEKS INTO HIS INVESTIGATION, Bundy found Jane Beaver, the woman who’d shown Cora Fisher the picture.

Come in, Beaver said at her trailer door, I will tell you what you need to know.

Beaver was 59 and worked two decades as a clerk and assistant in the accounting department at the University of Georgia’s research outpost on Sapelo Island. After a layoff in 1991, she started a home business, Ceramics by Jane.

She knew Perry, she told Bundy, because he’d dated her daughter. After they broke up, Perry stopped by their home. It was about three weeks before the murders. Beaver said Perry told her during that visit that he had asked Harold Swain to lend him some money. She said Perry told her Swain laughed in his face.

Then, according to Bundy’s report, Beaver said Perry told her this:

I’m going to kill that n-----.

DENNIS PERRY WAS LIVING NEAR Jacksonville, Florida, working construction. He and his wife, Karen, had been married seven years when Bundy showed up at their home on marshy Black Hammock Island.

The men spoke in the driveway, and Perry laid out his alibi: He was in the Atlanta area when the murders happened.

Bundy said Perry mentioned a detail that was significant: Harold Swain had the strong hands of a pulpwooder. But Perry also said he didn’t personally know Swain. How, Bundy wondered, would Perry know about the man’s hands?

It was well-known around Spring Bluff that Swain had owned and operated a pulpwood business, and that fact was mentioned often in news coverage of the murders.

Another day, Bundy spotted Kennedy pumping gas and pulled over. The men were familiar from when they both worked at the sheriff’s office. And Bundy knew how long Kennedy had toiled to solve the church murders. It seemed to Kennedy that Bundy wanted to hear his opinion on Perry.

Bundy pulled out a photo of Perry, with shoulder-length hair, that Jane Beaver had given him.

Ten years had passed since Kennedy and his partner investigated Perry, along with dozens of others. Kennedy didn’t remember Perry.

But after listening to Bundy describe what Bundy considered incriminating evidence, including Perry’s comment about Harold Swain’s hands, Kennedy remarked that the photo looked like the composite. He thought Bundy might be on to something.

WHEN BUNDY READ DOCUMENTS from Kennedy and Gregory’s investigation, he says he suspected they had tunnel vision on Donnie Barrentine and weren’t as open-minded as they should’ve been about Perry. Kennedy and Gregory would later wonder if Bundy had tunnel vision on Perry when he heard about Erik Sparre.

In November 1998, Sparre’s second ex-wife, Rhonda Minder, contacted the sheriff’s office. It had been 12 years since the family of Sparre’s first ex-wife played a tape for Kennedy in which a man she identified as Sparre said he’d killed the Swains.

Minder had information to share, too. A GBI agent assisting Bundy detailed her statement in a report.

One day in 1988, she said, Sparre held her down on the bed with a pillow over her face.

Don’t kill me! she screamed.

She fought free.

Minder brought up the church murders, though the report doesn’t say why.

You could have killed those people in Camden County, Minder told Sparre, according to the document.

This is how she said he responded:

Yeah, I could have killed those people.

The report doesn’t say if she knew why Sparre would’ve killed the Swains, but it says she called him a “white supremacist.”

Bundy and his GBI assistant pulled basic background info on Sparre but stopped looking into him within weeks, the case file shows. Bundy told “Undisclosed” that he dismissed Sparre as a suspect because Minder said he’d claimed to have used a shotgun to kill the Swains, not a handgun. But there is no record in the case file of Minder or anyone else saying Sparre used a shotgun.

When I spoke with her in 2019, she said something that wasn’t in the report of her talk with Bundy. She said Sparre told her explicitly that he had killed the couple.

BUNDY KEPT CHARGING TOWARD PERRY. The detective was close enough that his contract was extended.

On Jan. 13, 2000, nearly 15 years after the Swains died, Bundy succeeded. A grand jury indicted Perry on two counts of murder. Within hours, Perry was at a law enforcement facility in Jacksonville with three investigators, saying, again, that he was nowhere near Camden County on the night of the murders.

One of the investigators was GBI agent Ron Rhodes, who’d been brought in to help Bundy. Rhodes often recorded interviews and had a recorder with him. But the only record of what was said in that room is a written report by Rhodes. No one turned on the tape recorder.

Rhodes’ report says Perry said terribly damning things, including that he rode a motorcycle to Camden County with his brother days before the shooting and that he “could” have been at the church but “could not remember.”

“Agent Rhodes asked Perry if the gun went off by accident and Perry stated yes.”

“Detective Bundy asked Perry if he was scared this day had been coming for a long time and Perry stated yes.”

Then Perry said something that ended the interview.

“Perry stated, ‘you’re trying to put words in my mouth.’”

Only then did Rhodes ask Perry if he would make a statement on tape. He said no.

Perry and his attorneys maintain Rhodes’ report is inaccurate and misleading. If there were a recording, it would be clear exactly what Perry said and what the detectives had said to him.

“Unfortunately,” Perry’s trial attorney Dale Westling would later say, “we’ll never know what he was saying because three experienced police officers in the center of law enforcement in the giant city of Jacksonville, surrounded by electronic equipment, chose not to record it.”

WHEN KENNEDY AND GREGORY HEARD there’d been an arrest in the case, they were happy. Then Gregory recognized Perry’s name. He was the man they’d cleared 12 years earlier.

He called Kennedy.

We put his photo in a lineup, Gregory said.

Kennedy remembered. He felt sick.

The two both told the district attorney’s office they had cleared Perry. Now the state was seeking the death penalty.

AS PERRY’S TRIAL APPROACHED, the state offered him a deal.

If he would plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter, Chief Assistant District Attorney John B. Johnson III would seek a 10-year sentence with credit for the three years he’d already spent in jail. He’d even see to it that Perry was eligible for parole in just two weeks. That would be drastically different from the death penalty. (Johnson declined to comment for this story.)

Perry was hoping for an acquittal. He didn’t want a deal.

The trial to decide whether he should live or die began Feb. 10, 2003.

Bundy was critical to the case, but defense attorney Westling found a wide-open target in the deputy’s no-notes-or-recording method of interviewing. Westling questioned him with an incredulous tone and gave his style a nickname: “The Bundy Method.”

The method caused contention throughout the trial, but perhaps the most striking moment came when Bundy testified that Perry admitted that he was at the scene of the murders. Bundy said he remembered Perry telling him and the two other investigators this. Rhodes’ report says Perry said he “could” have been at the scene but “could not remember” — not that he was there. Neither Rhodes nor the Florida detective sitting in on the interview corroborated Bundy’s assertion in their testimony.

Cora Fisher, the church witness who’d told Bundy that Perry was the shooter, was too frail to come to trial. Her testimony, given in a deposition at a nursing home, was read aloud in court. Fisher said she recognized Perry as the killer in the photo Jane Beaver showed her, the one that made her faint. Fisher said something else about fainting: Ever since the murders, she fainted every time she saw “somebody white coming at me with long hair or any kind of hair.”

The defense chose not to attack Fisher for the curious sketch her memory had produced for an artist hours after the murders. Fisher’s suspect looked wildly different from the man in the three other witness sketches. During the deposition, when Perry’s attorney showed Fisher a photo of Donnie Barrentine with long hair, she said Barrentine was the killer.

Part of the defense’s strategy to prove Perry innocent was to prove Barrentine guilty. Perry’s attorneys called as a witness the inmate who in 1985 said Barrentine had boasted about killing a black couple in a church. The inmate testified that Barrentine said he and a “partner” had taken part in the murder plot. But Barrentine never gave the partner’s name, he said. (There’s no evidence Barrentine ever knew Perry or Sparre.)

Barrentine testified he was innocent, that he had no memory of confessing. (In 2019, he told me he might’ve done some crazy things while trafficking drugs, but he would never hurt someone at a church.)

The glasses found near the bodies couldn’t be explained by the state or the defense. Stuck in the hinge, investigators had found two hairs, but DNA tests showed the hairs didn’t belong to Perry or Barrentine. The same went for the car seen by at least two people outside the church. Neither man could be linked to a similar car.

Kennedy and Gregory testified about their efforts in the case.

Though he hadn’t been a deputy in a decade, Kennedy felt he was betraying the law enforcement community when he testified about problems in the state’s case. At the same time, he looked at Perry and felt nauseated.

Called as a witness by the prosecution, Kennedy told the court that he’d recorded interviews with key witnesses and had no idea why the tapes, like the eyeglasses and nearly all other physical evidence, were now missing.

Gregory happily testified for the defense about how he and Kennedy had cleared Perry in 1988. He was defiant with Johnson, as they went back and forth over missing evidence. Gregory estimated that four boxes of files and photos were gone.

A FORMER NEIGHBOR AND CO-WORKER of Perry’s was the linchpin to his alibi. Charlie Williamson testified that he drove Perry to and from work in College Park in 1985, including on the day of the murders. Williamson recalled seeing the sketch of the suspect days later. He said he kidded Perry because the sketch resembled him, but he knew Perry couldn’t have done it.

Williamson said they normally worked until 4:30 p.m. or 5 p.m. and the trip to Perry’s house in Jonesboro took an hour or more. Best case, Perry could’ve left Jonesboro at 5:30 p.m. With that timeline and ongoing roadwork on I-75, Gregory testified, it was “virtually impossible” to place Perry at Rising Daughter by about 8:45 p.m.

In the gallery, Perry’s relatives felt pretty good about his chances of acquittal.

But Jane Beaver’s testimony fell like a bomb.

She described what Perry allegedly said to her about planning to kill Harold Swain. She said her daughter didn’t hear it; she’d stepped out of the room.

“He told me that he asked the man for money, if he would loan him money to get back to Jonesboro,” Beaver said. She paused and used air quotes, saying Perry said Swain “put me down and made fun of me.”

“OK,” Johnson said. “Did Mr. Perry say what he was going to do to that man?”

“He said, ‘I always wondered what it was like to kill a n-----, and now I’m going to get me one.’”

The jury didn’t know — because the defense didn’t know — that Beaver was soon to be paid $12,000 in reward money for her testimony, as a document uncovered by “Undisclosed” proves. The jury didn’t know that even Beaver’s daughter, who’d dated Perry, didn’t believe Perry was guilty, as she told “Undisclosed.” The jury didn’t know that people close to Beaver, who died in 2018 after a 10-year fight with dementia, had for decades regarded her as someone who’d lost touch with reality after a series of personal traumas. The jury didn’t know the defense had lost a motion to compel the state health officials to turn over Beaver’s medical records, or that on the state’s copy of the motion someone wrote a curious note in pen: “Suffered from delusional problems — hallucinations — paranoia.”

The jury didn’t hear a word about Erik Sparre because all the investigators had dropped him as a suspect.

IN CLOSING ARGUMENTS, the jury heard Perry’s attorney complain about the missing records and evidence and say that Perry was proved innocent years ago by two good investigators. He said The Bundy Method was sloppy, that it was simply unbelievable that Bundy solved the cold case so quickly. He implied Bundy was motivated to rush so he could get his contract extended.

Johnson, a veteran prosecutor who had a reputation for winning high-profile and often controversial cases, told the jury he was thankful Kennedy and Gregory were never able to charge Barrentine because, if that’d happened, an innocent man might be in prison. He said The Bundy Method was sound. Though there was no record of it, Johnson said Beaver had come forward to Kennedy and Gregory decades earlier, and they didn’t “bother to call her back.” Though no one but Bundy remembered it, Johnson told the jury repeatedly that Perry admitted he was at the scene. That, Johnson stressed, was a confession.

When the jury returned the verdict, Perry’s wife cried in the gallery. So did relatives of the Swains; they thanked God for justice. Perry would later tell me how it felt: “It’s like someone reached in your body and snatched out your soul. My whole body was weak.”

Before the jury could begin to consider if Perry should die, Johnson made another offer: If Perry would waive his rights to appeal, the state would agree to two life sentences instead of death.

Perry had only minutes to decide. He wasn’t allowed to confer with his family.

His attorneys told him they suspected the jury would vote for death.

Perry took the deal.

IN PRISON, Perry began enduring identical days full of identical moments, where time, in fact, passed, but imperceptibly. He wrote poems and drew, read the Bible. He watched TV and worked in the commissary. He slept on a bottom bunk in a large, open dorm and kept mostly to himself.

After a few years, he divorced his wife. He didn’t want her to feel obligated to a life she hadn’t signed up for.

In 2007, Perry got a letter from Brenda Hahn, a woman he’d known in passing in Camden County. She recalled a night long ago when Perry gave her a kiss on the cheek outside a bar — a friendly thank you for a ride to the store. Perry was single that night; Hahn had just been married. But Hahn remembered that kiss.

Now she was divorced, too, and thinking of Perry. She believed he was no killer.

After exchanging letters, Perry called, prepared with a good opening line: Do you know who this is? It’s the rest of your life.

Crazy as it sounded to some of her loved ones, Hahn eventually decided she wanted to be with Perry. They married in 2009 at Autry State Prison.

Brenda became one of Perry’s most vocal advocates. She kept in contact with the Georgia Innocence Project, which had taken Perry’s case after receiving a letter from his mother, who died in 2017.

Brenda, who runs the cafeteria at Camden County High, got a new license plate: DBPERRY. Dennis and Brenda Perry. She talks often to co-workers about Dennis, how good a man he is, how patient and kind and loving, how much she wishes he could come home.

“People don’t realize what they have,” Brenda told me. “Sometimes when he calls, I just listen to him breathe, to know he’s all right.”

Dennis sends Brenda poems and crafts he makes. He tells her as often as possible how thankful he is for her. He listens to her cry and encourages her in all things. She is, he says, his soulmate, his world, his life, his “BFF” (best friend forever).

They talk about what they’ll do when — not if — he comes home.

“I dream of the day I’ll be able to hold my wife sitting on the creek bank and listen to the wind blow,” Dennis told me in a letter. “I’d like to find a field with just Brenda and I to drop to our knees and thank God for all his beautiful blessings and the deliverance he had provided us.”

For now, Brenda drives 90 minutes every Saturday to sit across the table from him for five hours at the Coffee Correctional Facility. Guards allow them a quick hug and kiss. They have never been allowed more than that even once.

Today they feel more hope than they have in a long time, because of discoveries made by "Undisclosed," which worked alongside Perry's attorneys. The habeas corpus petition sits before the Superior Court in Coffee County, where Perry is held in prison.

“Undisclosed” had covered so much ground in its 24-hour-plus season on the murders. It seemed daunting to me to find something new in a case that’s been investigated and reinvestigated over 35 maddening years. But “Undisclosed” mentioned Sparre only in passing, and the habeas petition didn’t mention him at all. I quickly found out there were still leads to follow, questions with answers.

Chapter 4

What Everybody Missed

On a rutted dirt road outside Brunswick, I steer into a yard with a sun-bleached bread truck parked next to a double-wide trailer. This is the home of a former longtime Winn-Dixie manager, a man I hope can help me find Sparre’s old boss.

Back in 1986, Kennedy and Gregory dropped Sparre as a suspect because his alibi checked out: He was working at a Winn-Dixie in Brunswick on the night of the murders. The report detailing the alibi contained a line that seemed surprising to me: The man listed as Sparre’s boss, Donald A. Mobley, told Gregory that several people remembered seeing Sparre at the store that night.

How many people could tell you what they were doing on a random day a year ago? Yet Mobley was saying that several employees could remember — a year later — seeing their co-worker on a particular evening?

At the trailer door, the man tells me he doesn’t know any Donald Mobley. His wife, who also worked at the same grocery store in the mid-’80s, says she doesn’t either. They do, however, know David Mobley, who managed the store back then.

Given David’s number, I stand in the couple’s carport and dial.

David Mobley picks up and listens to my questions. Yes, he says, he managed the Winn-Dixie at Brunswick’s Lanier Plaza from 1981 to June 1986. He can’t remember if Sparre worked there, but he says he knows he had no employee named Donald Mobley.

“I’m positive,” David says.

Had the investigator talked to David and accidentally written Donald in the case file? David says he has no memory of anyone ever calling to ask about Sparre or the murders.

It’s been 34 years. Perhaps David has forgotten, and the first name was a simple mistake. But if Gregory got David’s first name wrong, he also got David’s middle initial wrong.

And his home address.

And his birth date.

And his Social Security number.

And his home number.

And his work number.

None of them is even close.

And that’s not just David Mobley’s word. I also confirmed this by scouring public records and conducting various other interviews. I found that the Social Security number given to investigators by Donald A. Mobley belonged to a woman who died in 1978.

Through old telephone directories at a local library, I found that the phone numbers listed for Mobley’s work and home belonged to different people when Gregory wrote the report. Oddly, the work number, which ought to have belonged to Winn-Dixie, belonged to a widow. Her daughter told me she never heard of her late mother knowing anyone by the name of Donald Mobley. Asked if there was any chance someone could’ve used the phone, the daughter said her mom had a phone in the back shed that someone could’ve used.

Where did Gregory get the number to the Winn-Dixie? He doesn’t remember, but he says sometimes he would ask suspects for bosses’ phone numbers. Perhaps Sparre was the source of the phone number, Gregory says.

Then I tell Gregory something I learned from Sparre’s ex-wife Rhonda: Sparre used to change his voice and pretend to be other people on the phone.

Gregory sounds crestfallen. He grows quiet. In our previous conversations, he often criticized Bundy and others who he felt made errors in the case. In this moment, he seems to look inward as I ask, is it possible the person he spoke to all those years ago wasn’t a Winn-Dixie manager at all?

“That’s very possible,” Gregory says.

AFTER I TELL KENNEDY what I’ve learned about Sparre’s alibi, he sits reeling at the picnic table by the Satilla River. He progresses from shock to shame to regret to sadness in a matter of minutes.

He thinks of Perry. “God!” Kennedy says in anguish, slapping both knees with his palms, staring into the storm clouds over the river. “He’s been in prison all this time. Oh, my God ...”

Kennedy stopped drinking four years ago, at age 70. He started reading the Bible instead. He tells me he has health problems stemming from diabetes. He’s had a triple heart bypass. He keeps saying he wants to live to see this case resolved.

He thanks me for what I’ve discovered about Sparre’s alibi, for finding something he missed, because it gives him hope for the case to be set right.

“It may be something that takes this guy out of prison,” he says. “God almighty. It just seems like it opens up a whole new door.”

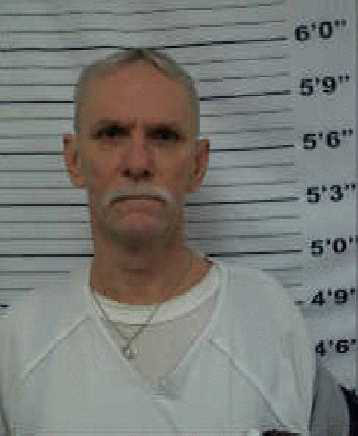

SPARRE CALLS ME ONE DAY IN FEBRUARY. The 56-year-old has just opened a letter I sent to the Brantley County home where he lives with his elderly mother, asking him to talk.

He says he is innocent, that he never told anyone he was guilty. He says he isn’t racist or violent.

He says he doesn’t even know where Rising Daughter Baptist Church is.

“I do not know the Swains. Never met them,” he says.

He remembers hearing rumors that the Swains were murdered because Harold Swain owed money to drug dealers.

I tell Sparre that multiple people told police that he’d said he was the killer. I mention that Kennedy’s report says there was a tape of him on the phone claiming to be the killer while threatening to kill his first ex-wife and her family.

Sparre still denies he said it and says his ex-wife was lying. (Emily died in 2013. Her brother Emmett Head, who a police report says heard Sparre say he killed the Swains, declined to comment for this story. The tape is missing.)

Sparre doesn’t mention an alibi, and in this conversation, I don’t either because I’m hoping to talk to him in person.

A few days later he calls back and sounds mad. He accuses me of coming to his house and taking a clipping of his mother’s hair for a DNA test.

Stunned, I start to realize what happened: After learning from me about the problems I encountered with Sparre's alibi, Perry's attorneys decided to check his mother's DNA against the lone DNA evidence in the murders: the hairs found in the hinge of the glasses.

Because the hairs were rootless, the only test that could be done was a mitochondrial DNA test, which can identify the maternal line of the person who’d lost the hairs. The hairs have gone missing, but the case file still contains the details of the DNA profile.

I assure Sparre I haven’t been anywhere near his house. On the phone, I can hear him smoking and occasionally spitting on the ground as we talk. This time he says he did tell his ex-wife Emily that he killed the Swains, but that he was only trying to scare her. This time he mentions an alibi. He says he was working at Shuckers, a seafood place on Jekyll Island.

Sparre says he is done talking with me and wants me to leave him alone. I haven’t had a chance to ask about his Winn-Dixie alibi, but he acts like he doesn’t need an alibi.

“This DNA,” Sparre says, “will prove that I didn’t do it.”

THE DNA DID NOT PROVE THAT.

The test shows that the hairs from the crime scene belong to someone in Sparre’s maternal line. Sparre is the only person in his maternal line known to have allegedly admitted he was the killer.

The test found that 99.6% of the North American population would not be a match. In other words, 1 out of every 250 people would match the hairs from the scene. A modern test of those hairs could produce more precise results, but the hairs have been lost since they were tested in 2001.

The test linking Sparre to the glasses is significant, said Simon A. Cole, a forensic science expert from the University of California, Irvine, who examined the DNA report for the AJC. The match is compelling, Cole said, especially when you factor in the other evidence about Sparre: two ex-wives describing him as a violent racist, his first ex-wife’s statement that he had glasses like the unique pair with the hairs in the hinge, Sparre’s multiple alleged statements about committing the murders.

It isn’t as though Sparre was a random man who happened to be a match to the hairs. He was a known suspect who was once caught on tape saying he murdered the Swains. And now he’s linked by DNA to glasses found inches from the victims’ bodies inside a church that Sparre says he has never been to.

“How unlucky does that (DNA match) make Sparre if in fact he’s innocent?” Cole said.

Perry's attorneys in late March took the DNA results to Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Jackie Johnson, whose office prosecuted Perry. Johnson’s office could have considered the evidence and asked a judge to free Perry, as other prosecutors have done when new DNA evidence brought convictions into question. The Georgia Attorney General’s Office, which was notified on April 1 of the DNA match, could also ask for Perry to be freed. Five legal experts I spoke with said that unless the state has some bombshell evidence to refute the DNA findings, the state should move to free Perry now.

The Georgia Innocence Project and the King & Spalding law firm filed a motion for a new trial on April 27. “The new DNA evidence is critically significant because it for the first time provides reliable forensic physical evidence linking a known suspect, Erik Sparre, to physical evidence at the crime scene,” the lawyers wrote.

On May 12 — six weeks after her office was notified of the DNA match — Johnson asked the GBI to reopen the investigation into the murders, citing the DNA. Johnson said she would use the GBI’s findings to decide how to respond the motion for a new trial.

As of May 14, Camden County Sheriff Jim Proctor and John B. Johnson III, the chief assistant prosecutor in the DA’s office who prosecuted Perry, hadn’t responded to requests for comment on the DNA match. Bundy, who retired from the sheriff’s office in September 2019, declined to comment.

Perry’s attorneys said they were disappointed it took six weeks for the case to be reopened, but heartened the GBI was getting involved. Brenda Perry had a similar reaction to news of the investigation. “That could take months,” she said with dismay.

In the new trial motion, the attorneys argue that Perry never would have been prosecuted had Sparre’s DNA been tested along with other suspects as Perry’s trial approached. Instead, the petitions says, the state “almost certainly” would’ve built a case against Sparre.

I CALL SPARRE on the day the motion for a new trial is filed. He apparently hasn’t been interviewed by law enforcement and doesn’t know about the DNA match. He tells me he doesn’t want to talk.

“I’m not going to sit here and go into all this. You got your DNA thing. That was you that came by and got that,” Sparre tells me.

Again, I make clear that the hairs were taken from his mother by the Georgia Innocence Project. I tell him the DNA was a match to hairs in the hinge of a pair of glasses found next to the bodies. “I want to see how you can explain that,” I say.

“Look, I have no idea,” he says. “I don’t have any glasses missing.”

I say his ex-wife told police in 1986 that he had a pair like the ones recovered at the church.

“I don’t know what she told them — and I don’t care. I want to be left alone. Leave me alone. Do not call me anymore.”

He hangs up.

NEWS OF THE DNA MATCH THRILLS KENNEDY.

“Prayer does work,” he says when one of Perry’s lawyers calls to tell him.

“I’m really happy,” he says when I tell him about the renewed GBI investigation.

The old detective knows people will ask why he and his partner didn’t test Sparre when they investigated him. The reason is simple: It wasn’t commonly done in 1986. DNA testing was in its infancy.

That doesn’t stop Kennedy from blaming himself. He recognizes that the DNA test could be the best evidence yet that he and Gregory failed in the investigation. They had Sparre. They let him go. That realization is crushing.

But he finds comfort in knowing the case may finally be solved. That was his job. His responsibility.

He still thinks about the Swains, how good they were, how terrible and unjust their ending. He cannot shake seeing them dead in the vestibule. He’s spent untold hours thinking of their final moments and how those seconds caused the community and their family so much hurt. The scene plays out in his head like an awful dream:

Before the gunshots, Harold realizes the man isn’t here for friendly reasons. Harold takes him on.

Harold loves to fish the Little Satilla River. He stops by people’s houses to see if they need help with anything, for no special reason.

Now Harold takes a bullet. He’s fighting the gunman with the strong hands that you get from a career in pulpwooding.

Harold’s Bible is still on his seat in the front pew. It’s turned to Ephesians 3, which is about Christ’s boundless and enduring love.

Three more slugs rip Harold’s skin. One woman in the sanctuary can see him slumped over, holding on to the killer. Thelma runs to help.

Thelma is a homemaker who makes sure to get all the work done in time to watch “Guiding Light.” She is funny, empathetic, loyal. When her niece Cynthia went away to college, Thelma made her a quilt to remind her of home.

The gunman fires again. Both husband and wife are wounded, together, as ever.

Harold and Thelma had been married 43 years. Just a day before the shooting, they went on a date to a new restaurant at the mall in Brunswick. When they found the place closed, they stopped by Cynthia’s house instead. She cooked them dinner, and Harold said her black-eyed peas were better than what the restaurant would’ve served. That little comment would make Cynthia smile every time she thought of it for 35 years.

Days after the murders, the Swains were buried in the small cemetery in the churchyard.

But in Kennedy’s mind, they’re still faceup in the vestibule, side by side, waiting for him to make sense of what happened.

This is a reconstruction of a 35-year old case. Reporter Joshua Sharpe reviewed the 6,000-page investigative file, listened to a 24-hour podcast and conducted dozens of interviews.

Dialogue appearing in quotes was either spoken to the reporter or is contained in transcripts of audio recordings or court proceedings. The AJC used italics in places where sources recalled the essence of what was said.

Joshua Sharpe grew up in Waycross, a South Georgia city planted on the edge of the Okefenokee Swamp. As a reporter for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, he has covered executions, the resurgence of meth, the failures of authorities to protect two children who were found buried in their backyard and the ravages of Hurricane Michael. Among the recognition his work has received is a 2018 Award of Excellence from the Atlanta Press Club.

Jan Winburn, who edited this story, teaches in the University of Georgia’s MFA program in narrative nonfiction. She specialized in narrative storytelling as an editor in newsrooms for 40 years. At The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, she edited the 22-chapter “Through Hell and High Water,” which reconstructed the epic battle of two hospitals to rescue patients during Hurricane Katrina, and “Chaplain Turner’s War,” which documented the life of an Army chaplain from Georgia during the Iraq War. Reporters she worked with have won the Pulitzer Prize, the Ernie Pyle Award, a Peabody, the Batten Medal for public service and the Livingston Award for Young Journalists.

This presentation was designed by Dave Young, Pilar Plata, Jason Foust and Pete Corson and copy-edited by Liam Miller. Additional editing by Janel Davis, Bill Rankin, Susan Hogan and Shawn McIntosh. Photography by Ryon Horne, Tyson Horne and Hyosub Shin. See AJC.com/alibi for entire project team.

Who’s Who

Harold Swain

A 66-year-old retired pulpwooder and deacon who was known around Spring Bluff for his generosity. He died in a struggle with the gunman at Rising Daughter Baptist Church on March 11, 1985.

Thelma Swain

A 63-year-old homemaker and mother known for her humor and kindness. She died after racing to help her husband fight off the gunman at Rising Daughter Baptist Church.

Butch Kennedy

The chief deputy at the Camden County Sheriff’s Office in 1985 and the lead investigator on the murders. He became a deputy to follow his father’s path. He retired before solving the murders, and the case has haunted him for 35 years.

Joe Gregory

The GBI agent who worked with Butch Kennedy on the case for years, running down thousands of leads and helping clear Dennis Perry as a suspect in 1988.

Donnie Barrentine

The suspect who most interested the initial lead investigators, partly because he had allegedly bragged about killing a black couple at a church shortly after the murders.

Dale Bundy

The former deputy who was rehired to investigate the church murders in 1998. He helped convict Dennis Perry.

Jane Beaver

The mother of Dennis Perry’s former girlfriend. Beaver set the case against Perry into motion by showing Perry’s photo to two women who’d been in the church during the murders. Beaver testified that Perry told her he was going to kill Harold Swain.

Dennis Perry

Lived in Spring Bluff to help care for his partially disabled grandfather but moved away four months before the murders. In 2003, he was convicted of murdering Harold and Thelma Swain based largely on the testimony of his former girlfriend’s mother. Perry is serving life.

John B. Johnson III

The longtime chief assistant district attorney of the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. He prosecuted Dennis Perry.

Erik Sparre

An early suspect who allegedly told his ex-wife he committed the murders. He was dropped from the case because investigators believed that his alibi checked out.

Emily Head Sparre

An ex-wife of Erik Sparre who told police in 1986 that he’d confessed to the murders.

Support for this investigation is made possible by our subscribers. Thank you.

Not a subscriber? Join us today.