Georgia businesses promised sweeping steps on race. How’d that go?

Last summer, when the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd sent everyday Americans streaming into the streets to protest racism, some of Georgia’s biggest companies decided to speak up.

They promised to fight discrimination by looking within their own walls, where half of the state’s 40 or so most prominent businesses had no Black directors on their boards in 2019.

Some committed to boosting diversity in leadership and increasing training to battle unconscious bias, while others said they’d up their donations to social justice groups. And some passionately talked about pushing for change in society as a whole.

A year later, many of those same companies say their latest effort to foster diversity and stand against racism is still a work in progress. But some people see reason for hope.

While there has long been pressure for the nation’s top corporations to be more inclusive, the events of last summer prompted some companies to take a more forceful stance.

Justin Short, an Emory assistant professor of accounting who co-authored a previous review of diversity on corporate boards, initially was concerned that companies were making hollow promises. But he said announcements about more board appointments of people of color — just one of many steps promised by companies — make him believe “what happened this past summer is going to effectuate real change.”

Other observers, too, say they have noticed a meaningful shift in some corners, though crucial gaps remain.

“What happened this past summer is going to effectuate real change."

“I’ve never seen such a systemic, significant, sizable and sustainable shift in the leadership mentality of the private sector, particularly publicly traded companies, particularly at the CEO level, in 29 years of me doing this,” said John Hope Bryant, who is Black and the founder and leader of Operation Hope, an Atlanta-based nonprofit that pushes for financial literacy and economic empowerment.

At the same time, there’s much debate about how politically active companies should be on social issues, from donating campaign dollars to taking public stands.

Home Depot, the biggest public company headquartered in Georgia, is facing a boycott for not forcefully and publicly opposing the state’s new voting law, with one boycott organizer promising more pressure in coming weeks. Critics of the legislation said it will make it harder for Georgians, particularly Black and low-income voters, to cast ballots, while proponents say the law expands access and makes elections more secure. And recently Coca-Cola endured negative ads for criticizing the same elections law changes, with one group saying, “serve your customers, not woke politicians.”

Many other major companies, including UPS, Southern Company and Aflac, have not taken a clear, public stance on whether they are in favor of or against the state’s voting law changes.

Meanwhile, a string of Georgia corporation this year were confronted with shareholder proposals for diversity audits, increasing board diversity and accountings of political giving. There were also campaigns to oust board members viewed as not taking aggressive enough action on the issues.

Eli Kasargod-Staub, the executive director of Majority Action, a nonprofit that called for the proposed measures, said he’s seen clear indications that boards at many companies are taking steps toward racial equity in the last year. But, he said, when businesses don’t curb giving to politicians who undercut equity, that “fundamentally undermines everything else those companies have been saying.”

A recent AJC poll, conducted by the University of Georgia after Major League Baseball pulled its All-Star game out of metro Atlanta because of the state’s new election law, found that about 60% of registered Georgia voters opposed corporations publicly trying to shape political opinion or promote cultural change. But a poll last November by GoBeyondProfit, a Georgia alliance of current and former business leaders, found that about 75% of employed Georgians want their employers to address racial and social issues.

Delta Air Lines and Coke say they’ve been working on a laundry lists of goals — from dramatically diversifying leadership and other ranks to mirror the general population, to doubling spending with Black suppliers — with hard targets, timetables, funding and internal and external actions. To broaden its workforce, Delta sharply increased the number of positions where it would accept job candidates with work experience rather than require a college degree.

“There is a long journey ahead to impact and sustain change,” Keyra Lynn Johnson, Delta’s chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer, said in an email.

Coke CEO James Quincey wrote last summer, “Simply put, America hasn’t made enough progress, corporate America hasn’t made enough progress and nor has The Coca-Cola Company.”

Home Depot, which generated $132 billion in revenue last year, offered a shorter public to-do list.

Initially, it said it would hold internal town hall meetings and give an extra $1 million to a civil rights nonprofit. It hasn’t set numeric goals for diversity in its employee or management ranks. A spokeswoman said the company expanded its unconscious bias training program to all employees. And the company’s foundation recently announced plans for job skills training programs for Black youths in Atlanta, Philadelphia and San Francisco.

Aflac, the Columbus-based insurer known for its quacking duck, didn’t layout specific plans or directly answer some specific questions posed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. But a spokesman emailed that “Aflac’s commitment to diversity and inclusion speaks for itself” and stated the company is “among the most diverse large companies in Georgia,” with leadership that is 23% minority and a board that is 36% minority.

Last year, UPS, like some other companies, said it would urge passage of a new federal anti-lynching law. Since expanding its training on unconscious bias, more than 99% of its managers have gone through the process, UPS said. The delivery giant also promised to give $4.2 million to organizations devoted to racial equity, education, business and advocacy. And the company pledged that its employees will spend a million volunteer hours mentoring and educating in some Black communities.

“We will be champions for justice and equality, not just in our words but in our actions here in the U.S. and everywhere we operate around the world,” CEO Carol Tomé said last summer.

Southern Company, the parent of Georgia Power, said it is committed to a workforce that mirrors the diverse communities it serves. It highlighted $200 million in giving it plans over five years to advance racial equity and social justice, and the company said it advocated to remove Confederate imagery from the Mississippi state flag. Southern also said it will leverage its political influence to advocate for policies that address systemic racism and will end support “for any official or organization that does not act in a manner consistent with” certain values, including honesty, fairness and diversity.

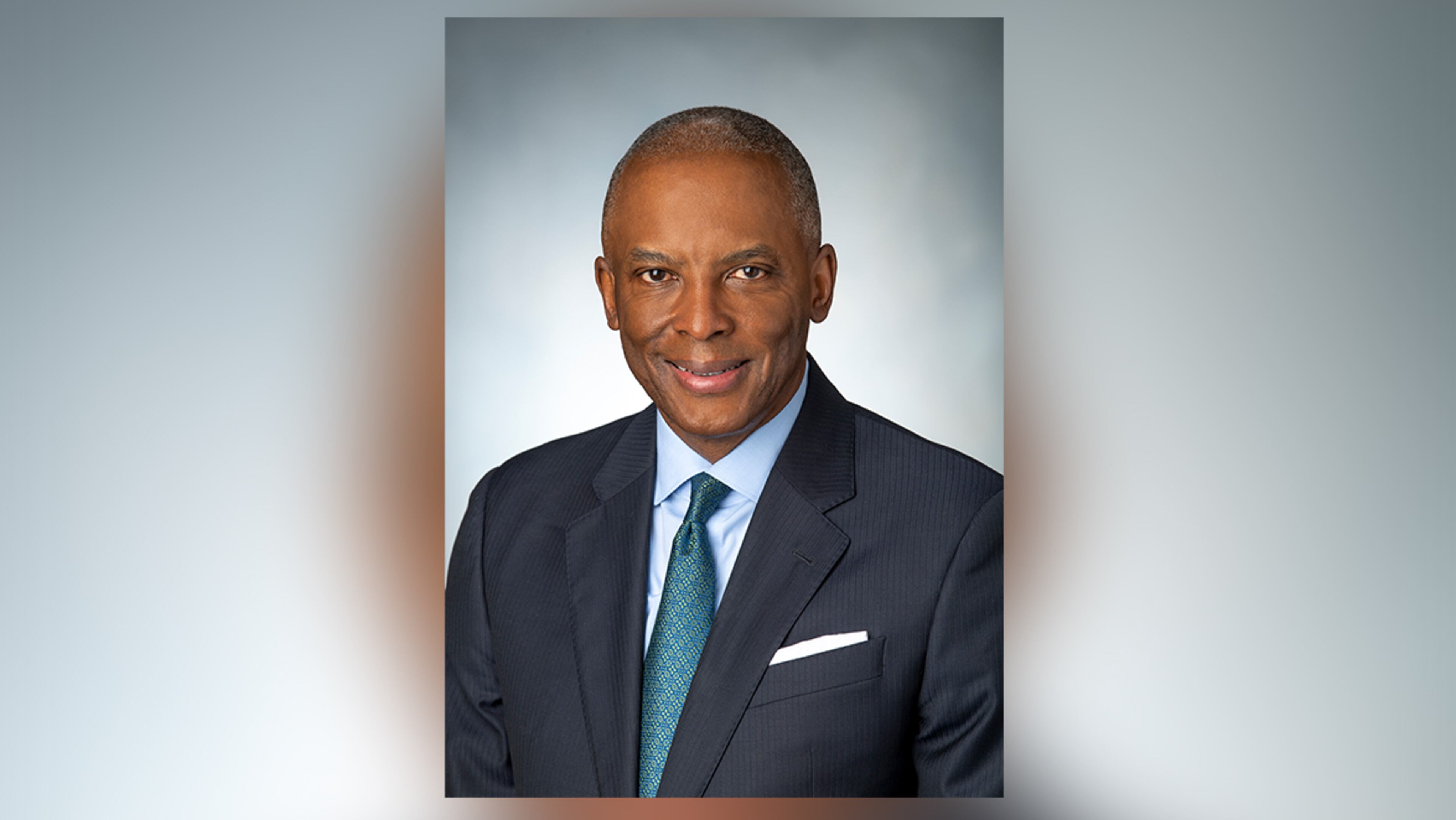

The moves are enhancements of efforts Southern has had underway for years, said Chris Womack, who this month became CEO of Georgia Power. He’s the first Black person to hold the position in the company’s more than 100-year history.

He characterized Southern’s previous diversity efforts as “good” but said they needed to be “much better.”

The company will continue to take steps, he said. “It could go faster, but I think the focus is making sure we are focused for the long haul.”

More broadly in metro Atlanta, he said, while minorities hold a number of senior level positions, “there is clearly more work to be done” in the highest ranks of Fortune 500 companies.

Corporate diversity programs and donations to social justice groups have been a part of the business landscape for decades. But change has come slowly for women and people of color trying to reach the very top jobs. Nationally, there are only a handful of Black CEOs at the 500 largest public U.S. companies.

Among the boards of S&P 1500 companies, Emory’s Short found evidence that Black directors accounted for 5% of the total national pool in 2019, up from 3% in 2008. Georgia had slightly higher percentages.

Still, he said, the percentages are much lower than the makeup in the overall population.

He hasn’t had access yet to full data indicating how much diversity on corporate boards may have changed in the last year. Companies generally aren’t required to disclose data on the race of board members. But some other measurements could become more accessible: This year, the biggest Georgia companies have committed to publicly disclosing breakdowns of racial and gender diversity in their employee ranks, including within leadership.

Bryant, the head of nonprofit Operation Hope, said CEOs are now coming to him for suggestions on how to make a difference on diversity and curbing racism. He said he recommends developing a decade-long commitment and embedding it deep in their business plan. CEOs aren’t flinching, he said.

In the past year, companies have committed many billions of dollars for social justice efforts, Bryant said. And he called out specific executives for praise, including Delta CEO Ed Bastian.

But more than dollars are needed, said Bishop Reginald Jackson. He said he is disappointed that many large Georgia companies, from Home Depot to Southern Company, didn’t publicly condemn recent voting law changes in the state.

Jackson, who heads the Sixth Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and helped lead a call to boycott Home Depot, said he thinks companies feared backlash from state legislators, such as those who tried to eliminate a tax break enjoyed by Delta.

He described being hopeful last summer when big businesses announced steps they would take to embrace diversity and battle racism.

“I am still optimistic,” he said. “But I still want to see more action.”