Atlanta airport on the front lines of wildlife trafficking crisis

The international airline passenger going through customs at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport didn’t seem suspicious at first. But an X-ray revealed two red-tailed boa constrictors coiled up inside his hollow-body guitar. The passenger claimed the crawlers must have slithered in while he was suntanning on a beach.

Charles Quick, senior wildlife inspector for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) office of law enforcement, was immediately alerted. From his office in a nondescript business park near the airport, he dispatched wildlife inspectors to retrieve the guitar. They brought it back, placed it on the conference room table, clipped off the guitar strings and pulled the snakes out. Today they live at Zoo Atlanta.

In his almost 17 years as a wildlife inspector, Quick said his proudest case wasn’t the snakes though; it was the skinks.

That time, U.S. residents traveled to Germany where they bought a pair of mating eastern Pilbara spiny-tailed skinks, a type of pumpkin-colored lizard that looks like a tiny dinosaur. The residents reported to customs they were bringing the skinks back to the U.S., so it was Quick’s job to intercept and inspect them. Before he did, he researched the species.

He determined that, at that time, eastern Pilbaras had only recently been discovered by Australian scientists. They are extraordinarily rare and are only found in Australia, a country that doesn’t allow the commercial export of reptiles for any purpose. Though Quick didn’t know how the skinks made it to Germany, he knew they made it there illegally. This also made them illegal to import into the U.S.

Quick seized the skinks and called Zoo Atlanta to take them in. The importers petitioned to get them back, but ultimately lost the case. The skinks did well at their new home at Zoo Atlanta where they later gave birth to multiple offspring. The surplus allowed Zoo Atlanta to send several of the lizards to other zoos across the country, advancing conservation efforts for the rare skinks.

“Pretty cool stuff … It was a real success story,” said Quick.

All in a day’s work

Quick is one of only three wildlife inspectors on staff at USFWS’s Atlanta ports of entry. His team includes Ashley Goodson, a senior field wildlife inspector for five years, and Desireé Smith, a new wildlife inspector who started in late 2023.

Together the trio is responsible for inspecting wildlife imports and exports coming through three zones: commercial cargo, express shipping and passenger planes arriving from international destinations. They also man the USFWS law enforcement office and work closely with USFWS agents who process fish and wildlife trafficking cases.

“We are very busy and we could use more people,” said Quick.

One day in April, Goodson and Smith took The Atlanta Journal-Constitution behind the scenes to get a peek at operations.

First stop was the commercial cargo warehouse on the grounds of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta airport. Goodson had flagged a shipment of tropical fish that had recently arrived from Thailand and was heading to a local pet store. With clipboard in hand, she was ready to check the shipment’s declared contents to compare it with what she found in the boxes.

She sliced open the first box and pulled out a clear plastic bag ballooned full of air and a fluorescent yellow liquid. Tropical fish floated in the bags appearing to be dead but weren’t. A chemical in the water, Goodson explained, put the fish to sleep for the duration of their travel. While this shipment was a declared import, the chemical is also sometimes used by illegal traffickers to keep fish from thrashing and evade inspection.

After checking the contents of a few boxes, Goodson sealed them with green and white tape to indicate they had been checked.

Next on her agenda was to meet a wildlife broker who was coming to the facility with an export of morph snakes ― snakes bred with genetic mutations to create unusual skin patterns. Wildlife brokers are licensed mediators allowed to transport fish or wildlife from their sellers to the secure airport export facilities, where they can be inspected before flying to destinations abroad.

Goodson ushered us into an empty back room where the wildlife broker wheeled in a cart loaded with coffin-sized cardboard boxes. Goodson sliced one open to reveal stacks of round plastic containers with coiled snakes inside. Next to the stacks were paper sacks containing snakes too large for Tupperware.

Goodson asked Smith to retrieve the snake tube, a clear plexiglass tube long enough for a snake to stretch out. Goodson put on her safety gloves, picked up one of the paper sacks with a long pair of metal tongs, secured it to the end of the tube with tape and shook the bag to coax the snake out. It slithered into the tube where she could see it. She reviewed the broker’s export paperwork and signed on the dotted line.

On Goodson’s checklist next was an inspection of hunting trophies. At a third-party shipping facility licensed to hold packages awaiting inspection, someone had shipped a car-sized crate containing prized kills from a hunting trip in South Africa. Mounted heads, horns and skulls of a water buffalo, baboon, hyena and oribi (a kind of small antelope) were inside. Goodson pulled out an undeterminable animal wrapped in brown paper.

When she opened it, the head of an enormous dead crocodile stared up at her with beady slit eyes. The crocodile’s body had been skinned with the head attached to create a rug. Goodson unfolded the skin on the warehouse floor revealing its mass.

For Goodson, Smith and Quick, most days are like this — checking shipments flagged to be inspected and making sure the proper paperwork is filled out. The paperwork helps countries track protected species coming in and out of ports. Occasionally, however, packages strike suspicion. An undeclared shipment might be picked at random. Or a tourist might get caught with something they shouldn’t have.

Not all things seized are alive, for example, a purse made from an animal skin, trinkets made from ivory or hats made with endangered bird feathers. But when wildlife inspectors do find illegal live specimens, the question always becomes what to do with them. And often they are found in bad shape.

“They’re poached from the wild, taken from their mothers, trafficked in horrendous conditions,” said Sara Walker, senior adviser on wildlife trafficking at the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). “They show up sick, weak, many of them don’t make it and are dead upon arrival … from a welfare standpoint, this is a crisis.”

Creating a confiscation network

Traditionally when live specimens are confiscated, wildlife investigators and the agents that prosecute the cases are responsible for finding them medical care and a home.

The system is inefficient, takes inspectors away from their primary job and relies too heavily on just a handful of facilities near the busiest ports of entry, said Walker.

“We have had overburdened wildlife inspectors and overburdened fish and wildlife service agents that have essentially been calling AZA members all the time desperate for assistance,” she said. “It’s been a system that is based on who knows who … and it certainly doesn’t cast a very big net.”

This is why, two years ago, the national Wildlife Trafficking Alliance (operating under the AZA since 2018) conceived of a plan to change the process for placing confiscated wildlife.

The Wildlife Confiscation Network was envisioned to provide one point of contact for wildlife investigators to call when they have live specimens. That contact would serve as a coordinator to handle logistics and determine the best place for the wildlife to go, ensuring no one facility is overburdened. It also widens the pool where wildlife can be placed; the AZA has 252 members nationwide and the confiscation network has begun vetting animal sanctuaries and other animal rehabilitation facilities across the country to become network approved.

A pilot program was launched in Southern California in 2023, and more than 4,000 specimens have been placed through the network so far, some to Atlanta facilities. Walker hopes legislation will expand the program nationwide, making the phone line available for all USFWS offices. But until then, Goodson, Smith and Quick will continue calling animal care facilities directly.

Atlanta facilities provide refuge

Georgia Aquarium, Zoo Atlanta and Atlanta Botanical Garden are three facilities Atlanta inspectors have turned to regularly with confiscations. Evidence of these partnerships can be seen on display at their facilities.

It can be seen in the touch pool at Georgia Aquarium where children eagerly dunk their hands into a shallow tank to feel the velvety backs of rays. In the pool are some Orangespot Freshwater Stingrays shimmying their bodies into the sand.

In 2017, seven Orangespot stingrays were given to Georgia Aquarium after a total of 39 were confiscated at Miami International Airport. The rays were the size of raviolis when inspectors found them packed in bags of water. Nine of the 39 rays were returned to Peru, 12 were shipped to other institutions and the remaining 12 died. For animals sensitive to changes in water quality and temperature, transport during trafficking creates significant stress on fragile bodies.

Adopting Orangespot rays is not cheap. Each one can live 15 to 20 years in human care and cost roughly $4,000 a year to keep healthy, according to a report by the Animal Confiscation Network.

“The kicker is we receive no federal aid to do this,” said Paige Hale, senior manager of communications for the Georgia Aquarium. “Zoos and aquariums have to pay for the care and the housing of these animals, otherwise they’ll be euthanized.”

Across the lobby from the touch pool is the Tropical Diver gallery, one of the largest living reef exhibits of any aquarium in the world. Hale shows off the tropical fish, mostly from the Indo-Pacific, and the colorful corals where they swim and dine. Many of the fish and coral species, she said, came to the aquarium via confiscations.

Coral confiscations, in particular, have been on the rise.

“We think it’s because during the pandemic people started aquariums at home and it became a hobby,” Hale said.

Globally, corals were the third-most confiscated wildlife group between 1999 and 2018, making up 14.6% of all seizures, according to a report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

While many types of coral are legal to import, vast quantities are being intercepted by USFWS because they are critically endangered, from an area of the ocean that is protected or lack proper paperwork. Wholesalers have also been caught hiding illegal corals inside shipments of legal species.

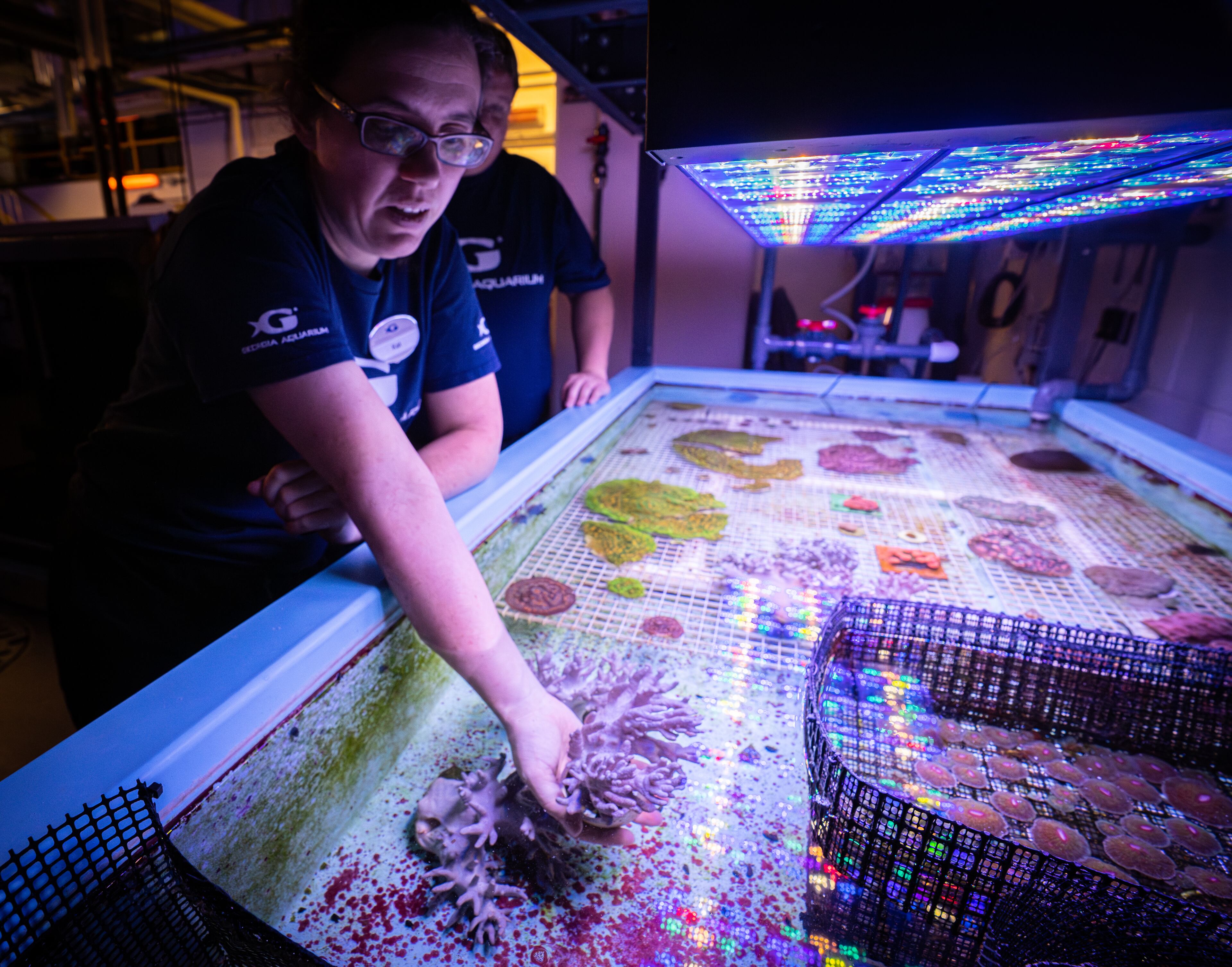

Steve Hartter, associate curator at Georgia Aquarium, is one of several staff members who work a 24/7, emergency phone line when USFWS has coral that needs rescuing. Time is of the essence, Hartter explained. When the coral arrives, it is often on the verge of dying.

Hartter gives tours of the coral triage area at the aquarium where designated tanks quarantine the sick coral and slowly acclimate it to new water conditions. He has developed a training program for students to learn the art of medical care for sick coral. Hartter proudly demonstrates how the tanks have fans overtop that blow water to simulate ocean currents and tidal flow. Bright lights installed above are key to keeping critical algae alive inside the corals.

Across town at Zoo Atlanta, Robert Hill, curator of herpetology, has also cared for many confiscated animals since he started working at the zoo 15 years ago. He’s personally cared for confiscated turtles, alligator lizards, snakes and other reptiles.

According to Zoo Atlanta’s registrar, close to 100 animals have come to Zoo Atlanta via confiscations since 2015.

“(These animals) not only become ambassadors for their species, but ambassadors for the plight of wildlife trafficking,” Hill said.

Ambassador animals are used at Zoo Atlanta to educate the public and promote conservation.

While the job of rehabilitating trafficked animals is rewarding, Hill said it is frustrating that the problem is still rampant.

“Law enforcement does everything they can,” he said. “But they’re just so understaffed that I feel it’s hard for them to keep up with how big this problem is.”

According to a report provided by USFWS, from 2015 to 2019, close to 50,000 live specimens confiscated at U.S. ports needed to be sent to facilities around the nation. That number, Walker said, only accounts for the wildlife found alive and placed.

Since USFWS primarily inspects shipments that have been declared, and because USFWS is limited in its inspection capacity (she estimates they only inspect 10% of shipments), far more animals are trafficked than represented by data.

“Take the scope and scale in the data and multiply it by thousands,” she said.

The U.N. and Interpol estimated in 2016 that the illegal wildlife trade is worth between $7 billion and $23 billion annually. Much of the wildlife trafficking problem wouldn’t exist without consumers. That includes those in biomedical research, the food trade and fashion, but the demand is mostly driven by the illegal pet trade.

“As horrific as this trade is, we need to understand that this is happening because there are people in this country who want these animals,” Walker said. “This really comes down to stopping the demand.”