In July and August 1996, the world sent its finest athletes to Atlanta. Some athletes came as familiar names from familiar nations. Others had toiled in obscurity. Each came proudly to Atlanta, and Atlanta received them in the same manner. To commemorate the 20th anniversary of those Summer Games, the AJC offers 20 memorable athletes and performances.

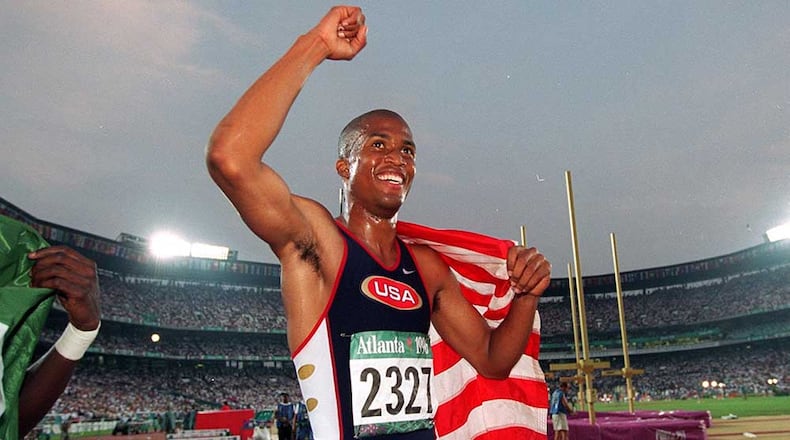

The fourth in the series: Derrick Adkins, who ran track at Georgia Tech, won the gold medal in the 400-meter hurdles.

Becoming the first local athlete win a gold medal in the Atlanta Olympics wasn’t a part of Derrick Adkins’ plan when he enrolled in Georgia Tech in 1988.

On a full scholarship, Adkins wanted to run for four years, earn his degree in mechanical engineering, and then trade his singlets and spikes for a suit and wingtips and join the corporate world.

“One thing kept leading to another,” he said.

It ended with Adkins taking gold in the 400-meter hurdles. It started, or rather the realization that he was an Olympic-caliber athlete started, five years earlier when he finished third at the U.S. championships, which qualified him for the world in Tokyo.

“That meant I had potential,” he said.

He tried to qualify for the U.S. team for the 1992 Olympics, but suffered an injury. Running through the pain, he finished fourth and failed to make the U.S. team.

Coming so close meant that he couldn’t retire. So, he committed to four more years of competing internationally and training with an eye toward the next Olympics.

He continued to improve, winning the Worlds in 1995.

“As years went by I continue to win accomplish my goals,” he said.

But the one goal was left: the Olympics.

He was the top-ranked hurdler in the world in 1994 and ’95. But he notes people don’t care if you are No. 1 or No. 100 if it’s not an Olympic year.

“If you want to make a name for yourself in track and field, you have to do it in a given window of time,” he said. “Knowing I may never have a chance to prove myself again, that puts a lot of pressure on Olympic athletes in track and field, swimming and gymnastics.”

He qualified for the U.S. team and came to his familiar Atlanta as the favorite in his race.

He acknowledges being anxious and nervous day and night for 2 1/2 weeks while in Atlanta before his race.

“It’s not a good feeling,” he said.

And athletes don’t want to be nervous because as adrenaline enters the bloodstream, everything moves faster. Moving faster can cause mistakes such as running out of lanes or hitting hurdles. Remember, this is not only a world-class athlete, but a mechanical engineer who also studied a little bit of biomedical engineering discussing the effects of anxiety. He was acutely aware of what was happening and what could happen.

He said he was very quiet throughout the day and night of the race.

“I just wanted to get it over with, win or lose,” he said.

Adkins started in lane 6, with rival Samuel Matete in lane 1, not a good place for hurdlers.

Adkins burst out of the start, grabbed the lead at the first hurdle, and carried it to a personal record of 47.54 seconds and the gold medal.

“I feel like I don’t have to win another race in my life,” he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution after the race.

He wasn’t done yet.

He tried to qualify for the 2000 team, but said he couldn’t maintain his speed.

He retired in 2001 and moved back to his native New York, where he stayed involved with track and field in a variety of roles.

“Now I live the life of a regular person,” he said, which was his original plan. “It’s refreshing. I get to look back and think about what I accomplished.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured