It took two distinct but complementary strategies to pull off upsets that flipped the U.S. Senate.

Jon Ossoff’s campaign quickly realized that the playbook he used to force a nine-week runoff against U.S. Sen. David Perdue wouldn’t win the overtime contest, so the 33-year-old orchestrated a shift to aggressively reach out to Black voters and other diverse Georgians to turn out.

Raphael Warnock had a different dilemma: For most of 2020, he went largely unscathed by Republicans as they battled each other for a spot in the runoff. Once the matchup was set, he had to fight a torrent of attack ads unearthing his past sermons and stances while still appealing to a base of voters.

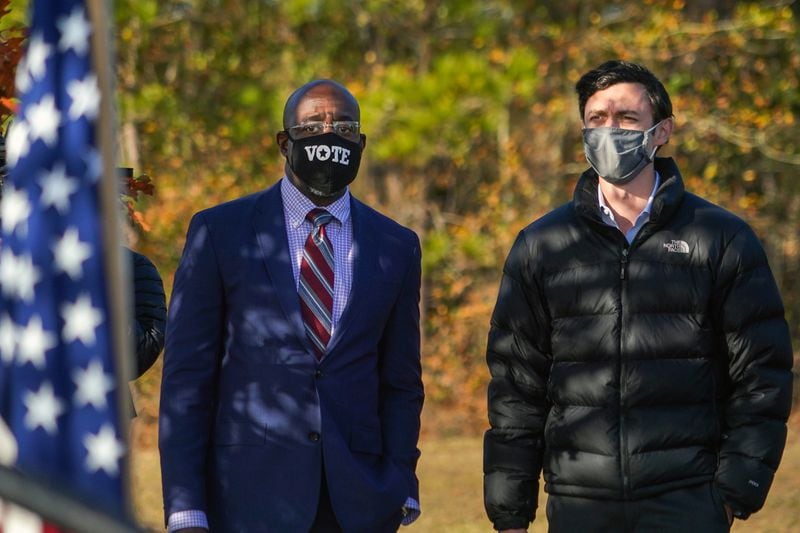

Their two approaches dovetailed on the campaign trail, where they ran as a joint ticket: Warnock reminding audiences of his path from Savannah’s public housing projects to the pulpit of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s church; Ossoff recounting his journey as a young Jewish protégé of John Lewis.

But they also overcame uniquely different challenges in defeating Perdue and U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler, pursuing strategies that emerged in fuller detail through interviews with key campaign operatives over the course of the week.

After ending the November election trailing Perdue by roughly 88,000 votes, Ossoff and his top advisers recognized they needed to significantly boost turnout among Black voters who tend to sit out statewide runoffs at higher rates than white Georgians.

“We knew we couldn’t run the same race again,” one aide said. “We needed to run a different playbook. And we had to inspire more Black, Latino and Asian American voters.”

Ossoff’s campaign built an infrastructure of 2,000 predominantly Black Georgians to mobilize voters, urging them to press their social ties to embrace his message of social justice and public health expansion.

Ossoff ran a half-dozen ads centered on Black voters’ struggles with injustice and the coronavirus pandemic. The ads highlighted how the pandemic disproportionately sickened African American families and invoked his support over the summer for demonstrations demanding racial equality.

And he returned to the anti-corruption narrative that he used to shape the launch of his campaign, which one aide described as a “match made in heaven between a candidate and a message” as Perdue came under fire for well-timed stock transactions and federal scrutiny.

That fed into Warnock’s line of attack against Loeffler, too, though overall the Democratic TV messages were more optimistic than the GOP messaging — a blitz of commercials claiming the two challengers were “radical socialists” and, in Ossoff’s case, an agent of China.

Credit: Hyosub Shin/AJC

Credit: Hyosub Shin/AJC

It baffled some Republicans. Shortly after the runoff defeats, former U.S. Rep. Lynn Westmoreland noted that the airwaves and mailboxes in his neighborhood were jammed with ads “all about fighting socialism and China” — attacks he said were overblown.

“Democrats attacked on insider trading and corruption. Their messaging resonated more,” said Westmoreland, a Republican.

“I really don’t think most Americans really believe that stuff about socialism,” Westmoreland said, “and that money may have been better spent driving out more conservative voters.”

‘Meltdown’

President Donald Trump loomed over both contests with his false claims of a “rigged” election in November and stoked internal conflict that divided state Republicans. Though the Democrats peppered him with criticism, their campaigns were more focused on painting an image of a post-Trump world.

Republican strategists estimate that roughly 114,000 core GOP supporters who voted in November skipped the runoff, and several blamed Trump’s mixed messages and ceaseless attacks on state Republican officials for the drop-off. Democrats are quick to agree.

“When Trump’s not on the ballot, Republicans have a turnout problem,” said Lauren Groh-Wargo, a top aide to Stacey Abrams and head of the Fair Fight voting rights group, which led a stampede of fundraising and organized grassroots efforts for the dual contenders.

“Their party is going through an internal meltdown,” Groh-Wargo said. “What happens to the Republican Party when too many of their supporters are living in a disinformation propaganda stew? I don’t envy their challenge right now.”

Trump also figured in the Democrats’ economic message. They had been calling for $2,000 stimulus checks for months when Trump added his voice to the demand — and chastised fellow Republicans who didn’t heed his call. The senators endorsed the idea a week before the election.

Credit: wire

Credit: wire

Ossoff and Warnock were backed up by a massive state party effort that marshaled the combined might of the campaigns. Thousands of staffers and more than 40,000 volunteers made more than 25 million voter contacts, including through texting, calling and door knocking.

That amounts to 10 different contacts for each of Biden’s 2.5 million voters, with a particular focus on Hispanic, Asian American and Black voters who don’t regularly vote in runoffs.

“We made sure we contacted each voter that helped make Georgia blue in the first place,” said Jonae Wartel, the state Democratic runoff director. “The state turning blue gave us a tremendous amount of momentum, and we made it clear to people that their vote mattered.”

‘One step ahead’

Warnock had a different sort of challenge. Loeffler and her main Republican rival, U.S. Rep. Doug Collins, traded scathing fire for much of the year, leaving Warnock to consolidate Democratic support untouched.

Behind the scenes, Republicans were building an enormous book of opposition research to unleash on Warnock during the runoff.

The pastor’s campaign knew what was coming. His operatives, too, had mined hundreds of hours of tapes to find the most potentially damaging remarks — and were quietly preparing to defend against them.

Long before Warnock entered the race, his consultants urged him to “remain the reverend” throughout the campaign — sharing his life story, explaining his moral character and activist background, and promoting his personality to make Georgians feel like they knew him.

That strategy was on display in a relentless TV campaign. Warnock’s strategists made 74 ads between Aug. 20 and Tuesday’s vote, but the bulk of them — 64 — aired during the runoff phase. Most feature Warnock speaking directly to the camera.

“It was purposeful. People formed a relationship with him,” said Adam Magnus of Magnus Pearson Media, one of his key consultants. “We knew that the negative ads were coming, and we needed enough people to feel like they knew him and would stay with him to win. Ultimately that happened.”

It started with an early November ad portraying Warnock as a dog lover, in part to mock the coming attacks. As Magnus put it, it was a pivotal engagement in the runoff ad wars that was won with the message that “this is coming — so don’t be fooled by it.”

Warnock’s advisers also readied responses for the salvos: “We were always one step ahead,” Magnus said.

When Republican ads invoked Warnock’s past defense of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, whose sermons became a flashpoint in Barack Obama’s 2008 bid for the president, his campaign countered by airing a spot highlighting his work against hate.

Another attack ad claiming Warnock disparaged the military was swiftly met with a 30-second spot featuring the candidate with a picture of his father, a military veteran. Other ads featuring Loeffler’s visit to his church were used to blunt broadsides that he was a radical.

“We were given great gifts from the other side,” Magnus said. “They allowed us to go untouched until Nov. 3 because they made the strategic bet that they were going to be able to convince people of their version of Raphael Warnock during a runoff campaign. And it failed.”