The Allman Brothers Band history reads like an Italian opera, with death, betrayal and reconciliation played against a background of worldwide fame, rapturous fans and stunning music.

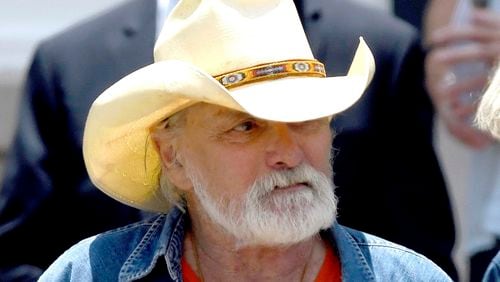

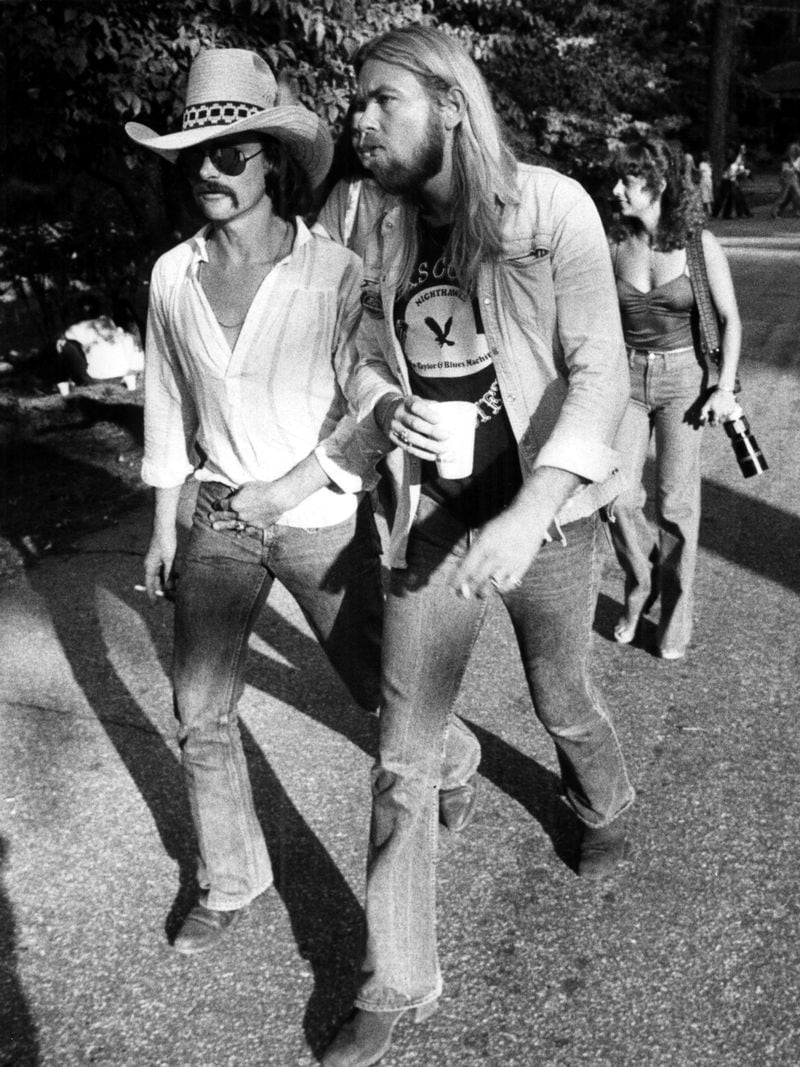

At the center of the action was Dickey Betts, resplendent in cowboy hat and “Viva Zapata” mustache, co-founder of the band and one half of the twin-guitar magic that gave the ensemble its signature sound.

Though the band wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for Betts, he was essentially invited to leave in 2000, at the beginning of its last incarnation. He never reconciled with the group even up to the moment they played their farewell concert in 2014.

Credit: Jerome McClendon

Credit: Jerome McClendon

Despite (or perhaps because of) personnel changes and the turbulent ups and downs of a band that seemed to die and resurrect itself every five or 10 years, the Allman Brothers generated a devoted following and a well-earned reputation as one of the greatest live experiences in rock ‘n’ roll.

Many fans took the drama in stride. Said Kirk West, longtime tour manager and ABB archivist, “I used to say if everybody got along it would be the Doobie Brothers, not the Allman Brothers.”

Betts, 80, died Thursday at his home in Osprey, Florida, after dealing with cancer and other health setbacks for several years.

Though Betts was with the band more than 10 times as long as co-founder and slide guitarist Duane Allman, he remained slightly in the shadows compared to Allman, even when it came to the name of the band.

Said band biographer Alan Paul, “The band had a name. It was named after two people. And he wasn’t one of them.”

Paul added, “I never heard him say he regretted that name, but he did.”

This is the paradox of Dickey Betts.

He was a co-founder of one of the most spectacular performing bands in American music, a group that had to be heard live to be appreciated.

His band became known for not just great songs, but a new form of group improvisation, in which the members followed each other through changes in tempo and dynamics, turning suddenly together like a school of happy fish, propelled by invisible telepathic communication.

Though they played three-minute hit-worthy tunes, their shows often expanded individual songs into concerto-length compositions, mini-symphonies that built to powerful peaks and subsided, only to crest again.

Their 1971 recording “At Fillmore East” (widely regarded as one of the 10 greatest live albums in rock ‘n’ roll), captured this dynamic beautifully, especially in the 23-minute version of “Whipping Post,” which occupies the entire fourth side of the double album.

Betts’ hand is visible in the armature that holds these “jams” together. A songwriter, Betts understood structure and pacing and how to tell a story.

That same sense of dramatic flow powered his improvisations. “Dickey’s soloing is really reflective of his compositional approach,” said Paul. “That he is a great songwriter kind of comes out in his soloing, which has a very coherent beginning, middle and end. It never sounds like he’s just noodling.”

Playing together, Betts and Allman took on the roles of melodist and harmonist. Betts threw down a melodic line, and Allman, with his perfect ear, spun out harmony lines on the fly. The two created an intertwining lead sound, with echoes from western swing, a new invention in rock ‘n’ roll.

“For me they are conversationalists,” said Bob Beatty, author of “Play All Night!: Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.” “I feel like sometimes I’m eavesdropping on their conversation.”

It was the mesh of the two that made Allman Brothers Band music intense and unforgettable. For that reason, the concept of ranking the two according to ability is a meaningless exercise. In fact, the entire band played like a single creature with 24 limbs and six heads.

Yet Duane Allman, after his 1971 death in a motorcycle accident at age 24, ascended to mythic status. Betts was rarely afforded the same reverence.

Paul said he thought the guitarist’s drinking, his sometimes erratic performances and confrontational attitude may have affected the public’s estimation of his ability.

“Dickey has his demons, which were really well documented,” said Paul. “Dickey’s bad side came to dominate the news about him and thus the perception about him. It’s very one-dimensional, and Dickey was not a one-dimensional person at all.”

It is a measure of Betts’ determination that, after Allman’s death, he was willing to go on the road as a five-piece band to fulfill their obligations, and even took up slide guitar to cover some of Duane’s parts.

According to West, that transformation surprised everyone. Said Gregg Allman to West: “I don’t know what the hell happened, but Dickey Betts learned how to play slide between Macon and New York City.”

“At Fillmore East” had been released just months before Duane Allman’s death and was beginning to see significant sales, which they were hoping to boost.

Credit: Chuck Leavell

Credit: Chuck Leavell

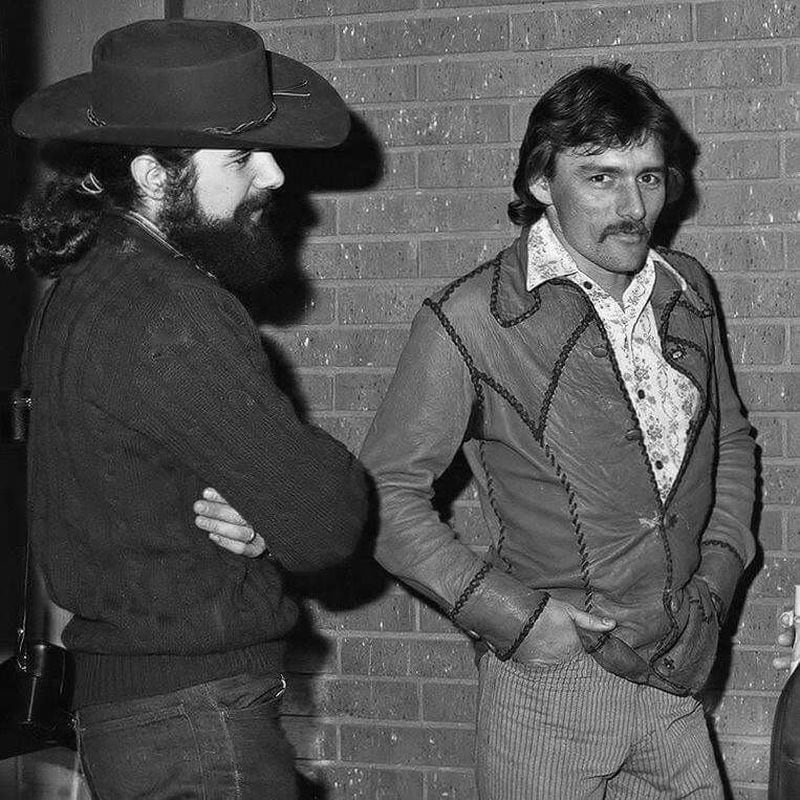

“Imagine the pressure that was down on Dickey,” said pianist Chuck Leavell, a fellow Maconite. “He had never played slide.” The band’s dark cloud got darker in 1972 when bassist Berry Oakley died in a motorcycle accident eerily similar to the one that took Duane Allman, and only three blocks from the same intersection.

Gregg Allman took off to work on a solo album, and Betts began playing, simply for therapy, in jam sessions that soon included Leavell.

Leavell eventually joined the band and is a significant presence in the band’s fourth album, “Brothers and Sisters,” from 1973.

The album generated the band’s highest commercial success, selling seven million copies. Betts was the de facto leader of the group at that point and wrote the majority of the songs for the album, including the transcendent instrumental “Jessica,” featuring Leavell.

The record also included the band’s only Top 10 hit, “Ramblin’ Man,” which Betts both wrote and sang.

Surely this peak demonstrated that even though his name wasn’t Allman, Betts was just as important to the Allman sound as Duane. Yet it’s significant that while “Ramblin’ Man” was climbing the charts, Betts was pursuing a solo project, “Highway Call,” a Capricorn Records disc that would, for the first time, bear his own name.

Credit: AJC Staff

Credit: AJC Staff

Atlantan Mark Pucci, Capricorn’s publicity director at the time, traveled with Betts on a promotional trip to New York, and said “The thing I remember about that trip is he was genuinely excited about the fact that he was doing his own thing, on his own album, in his own band.”

In the meantime, the ABB was on a roller coaster. The band broke up in 1976, reformed in 1978, dissolved in 1982, and gave it another go in 1989. During the 1990s, Betts’ drinking made him less reliable, and performances were tense, according to those close to the band.

Finally, in 2000, before a summer tour, the three original members of the band, Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, and drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson, voted to require Betts to go through rehab before joining the tour, according to Paul. “Dickey responded by filing arbitration against them.”

And that was it.

Subsequent to that event, after Betts was no longer in the band, the ABB avoided playing the song “Ramblin’ Man,” said Leavell.

Leavell thought that decision was wrong-headed and perhaps spiteful. “I thought: What are you guys doing? ‘Ramblin’ Man’ is a great song! You should be proud you were a part of it.”

By then bassist Oteil Burbridge and guitarists Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks (nephew of original member drummer Butch Trucks) had replaced Berry, Dickey and Duane.

Derek Trucks is part of the second generation of the Allman family, which also includes Bett’s son Duane Betts, a dead ringer for his father. The younger Betts has performed with his father’s band, Great Southern and also with Devon Allman (Gregg’s son) and Berry Oakley Jr. (Berry’s son).

Credit: Ben Gray / ajc staff

Credit: Ben Gray / ajc staff

Fans embraced the new version of the Allman Brothers Band and its virtuoso front line. Its recorded output was scant, but its concerts were legendary and remained strong until the band’s last show in 2014.

Betts’ death last week may bring about a re-evaluation of his contributions to the group and to rock ‘n’ roll, but many of those closest to the band never doubted his significance.

Among those is West, whose close relationship with Betts ended in 2000.

“Betts, he was one of my heroes, man, and the fact that we ended our lives not talking to each other for a decade or more, it’s a sad thing. But that’s the way it goes.”

Yet West remained a fan. “Dickey could write ‘Desert Rat Blues’ and ‘In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,’ which were two completely opposite representations of American music,” said West recently. “A redneck, kick-your-ass, rock ‘n’ roll tune and a beautiful, mystical, ethereal instrumental. If you take those two aspects of what Dickey could create, that’s all you need to know about Dickey.”