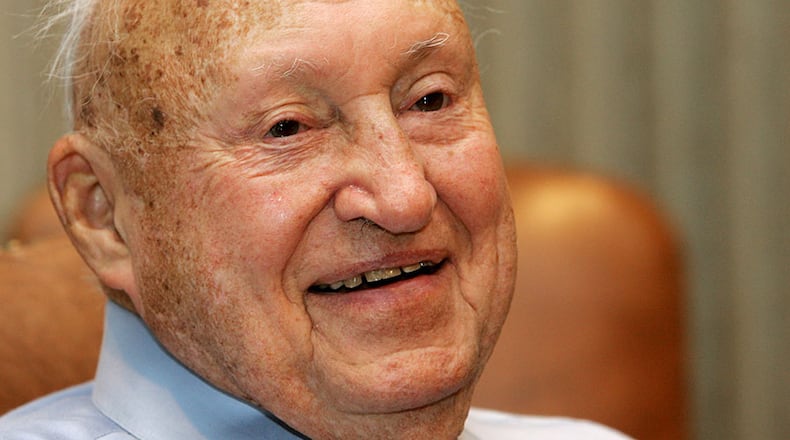

S. Truett Cathy, who turned a humble hometown restaurant featuring a boneless fried chicken sandwich into the Chick-fil-A juggernaut, died Monday at 1:35 a.m. He was 93.

Cathy, who died at home surrounded by loved ones, was known as much for his Christian principles — Chick-fil-A’s are closed on Sundays — as he was for his business acumen. He lived long enough to see his company rise from a local grill to the No. 1 U.S. chicken chain this year.

In many ways, he lived the American dream. Starting life in poverty, Cathy opened a tiny diner on the outskirts of Atlanta and built it into into a corporation with more than 1,800-restaurants. He was inspired as a teen by Napolean Hill’s motivational tome “Think and Grow Rich,” whose mantra was — you can achieve whatever your mind can conceive.

“I had a low image of myself because I was brought up in the deep Depression,” Cathy said in a 2008 interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “I struggled to get through high school. I didn’t get to go to college. But it made me realize you can do anything if you want to bad enough.”

His success, personality and principles made Cathy a rock star among fans who showed up in the hundreds at signings for the books he wrote or to hear him lecture on the fast-food industry.

Devotees would swoon when he spoke about his early years as a Hapeville restaurateur and the origins of his marquee chicken sandwich, while business leaders would pay rapt attention to his instructions on commitment to quality. His company was the envy of peers for its superior service — the phrase “my pleasure” is almost inextricably associated with the chain — and for its long-running, iconic advertising compaign featuring spell-challenged bovines.

There were some missteps along the way. Cathy tried to grow the brand internationally with stores in South Africa, only to retreat. The company’s Christian identity also rubbed some the wrong way, with accusations and lawsuits that claimed the chain discriminated against non-Christians, gays and others with different viewpoints.

And some in the business community questioned the privately-held company’s wisdom in closing on Sunday, a potential loss of billions of dollars in annual revenue. The genial Cathy stuck to his guns, explaining that it was more important that Sunday be a day of rest for the company’s workers and customers.

Operating six-days a week, the company had sales of $5 billion in 2013 and toppled KFC a year earlier as the top U.S. chicken chain, though KFC is larger in worldwide sales.

Over the past few years, as his health deterioated, Cathy had slowed down and trimmed his public appearances. Late last year, his son Dan Cathy, who had been the company’s president, was promoted to chief executive officer and chairman while his father was given the title chairman emeritus.

But to most, Chick-fil-A will always be connected to its colorful founder.

Cathy began tinkering with boneless chicken at his hamburger haven, the Dwarf Grill (now Dwarf House) in Hapeville, which opened in 1946 largely to serve nearby Ford plant workers. He spent four years devising the ingredients for his famous sandwich, which he began selling in 1961 before the ultimate formula was settled.

The motorcycle-riding, God-fearing Cathy resisted the temptation to take the company public. He was afraid a board of directors would unload him for not maximizing profits. And he wanted free rein on charitable ventures, which included sponsoring foster homes, summer camps and academic programs.

Cathy also didn’t want to change his policy of closing on Sundays. That started when he drew the shades at the Dwarf Grill once a week to preserve time for courting the woman he would marry.

“If it took seven days to make a living with a restaurant,” he once said, “then we needed to be in some other line of work.”

It is a policy embraced by his children — Dan, Don “Bubba” Cathy and Trudy Cathy — and is being passed to his grandchildren.

Former President Jimmy Carter, a Cathy friend, described the restaurateur’s faith: “In every facet of his life, Truett Cathy has exemplified the finest aspects of his Christian faith… . By his example, he has been a blessing to countless people,” Carter said in a statement. “We are fortunate to be among those whose lives he has touched.”

Named after preacher-evangelist George W. Truett, Samuel Truett Cathy was born on March 14, 1921, sixth in a family of seven children.

His dad was a struggling insurance salesman. The family made ends meet with Mom renting out beds at their modest home on Oak Street. Her work ethic was such that Cathy claimed the first time he saw her eyes closed was when she lay in a casket.

He got this start in the food business at 8, with her help. He erected a Coke stand in the front yard and chilled the bottles with frozen chunks of ice bought from an ice man who came by on a horse-drawn carriage. He would buy a six-pack of “Co’colas,” as he called them, for a quarter and sold them for 5 cents each, netting him a nickle for every six-pack. He was at the time a poor boy wearing shoes stuffed with cardboard, according to his book, “Eat Mor Chikin: Inspire More People.”

Winters, when demand for a frosty soft drink waned, he switched to magazine subscriptions.

He served in World War II and came home to build, with his brother, Ben, the Dwarf Grill between the Ford plant and Candler field, which became Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. Cathy continued running the restaurant, named for its petite size, after Ben’s untimely death and began experimenting with the “chicken steak” sandwich that has become the chain’s beloved hallmark.

He was an early entrant into newfangled shopping centers called malls, and opened his first free-standing restaurant in 1986 on North Druid Hills Road. The rest is Chik-fil-A history.

He made no bones about structuring his operation around biblical principles. Monday mornings at corporate offices begin with optional devotionals.

“I see no conflict whatsoever between Christianity and good business practices,” he said in 2006. “People say you can’t mix business with religion. I say there’s no other way.”

“People appreciate you being consistent with your faith,” he told an AJC reporter . “It’s a silent witness to the Lord when people go into shopping malls, and everyone is bustling, and you see that Chick-fil-A is closed.”

In later years, Cathy shifted his energies to charity — mainly foster homes and home for abused and neglected children. And he launched the WinShape scholarship program at Berry College, mostly bestowed to young Chick-fil-A employees.

The family torch has been passed to a second generation of Cathys. In early 2006, grandson Andrew Cathy began operating a franchise in St. Petersburg, Fla.

At the grand opening, the family and business patriarch said, “It was the best day of my career.” He expressed the wish that his other grandkids would carry on his vision.

“ I feel confident they will make it work for the next generation,” said Cathy, 84 at the time. “I’m not going to be around forever.”

He is survived by his wife of 65 years, Jeannette McNeil Cathy; sons Dan T. and Don “Bubba” Cathy; daughter Trudy Cathy White; 19 grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren.

Chick-fil-A said the public will be able to pay respects to Cathy at two public viewings and a public funeral service. The times and dates for those events have not be finalized.

In lieu of flowers, the family asked that donations be made to the WinShape Foundation, which was founded in 1984. Donations can be sent to: WinShape Foundation, 5200 Buffington Road, Atlanta, GA, 30349.

Former staff writers Mike Tierney, Gayle White, Maria Saporta and Joe Guy Collier contributed to this story.

About the Author